Agroecological Apple Juice Value Chain 2025

SDG Indicator 2.4.1 and SDG 12 Impact Case Study

Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 12 Target 12.3 – Indicator 12.3.1 – Sustainable consumption and production – provides the requirements –

By 2030, halve per capita global food waste at the retail and consumer levels and reduce food losses along production and supply chains, including post-harvest losses

Continuing the Journey of Sustainable Value Chain Development

Last year, 2024, was interesting since we were able to undertake a Value Chain case study with farmers to create products which are not just based out of Agroecological production and close to the primrary produce, but also create impact on SDG Indicator 12.3.1. It was also the first year we started formally executing – what we now call ‘MoolyaSHIKHAR’ True Price Accounting methodology for price discovery of Agroecological Produce for farmers.

This year also we are undertaking this market linked case study with Small and Medium Apple Producers in the Spiti Valley for the Juicing. The Labels QR scan to the actual farmers who are under the Government of Himachal CETARA-NF certified evaluation system for natural farming. Thus this directly impacts SDG Indicator 2.4.1 – Land Under sustainable and productive Agriculture.

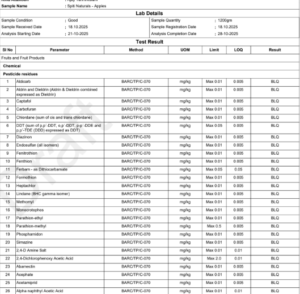

We also undertook residue testing at for the Apples this year for a set of 233 Agro-chemicals after procurement for sale and juicing. None of these were detected for the produce.

While this is an expensive step for marketing it is also a mark of assurance to uphold the guarantee from 2/3-star rated farms we support.

While Dr YS Parmar University of Horticulture and Forestry also introduced a new private collaboration venture on Value Chains including Bottling, we were unable to repeat the effort this year due to reasons (and delays) outside out control this year. This also impacted to optimality of the apples we utilised for juicing. However, this setback also lead to surprising alternatives and outcomes.

The 2025 season provided an opportunity to carry out a similar practical exercise with the Spiti Farmers at the HIMCO Juicing Plant located at Shamshi in Kullu district of Himachal Pradesh. This experience was aimed at further strengthening the understanding of how value chains are developed around horticultural produce that otherwise faces market rejection, post-harvest losses, or low economic returns for farmers. While the underlying objective remained consistent with the previous year minimizing waste and creating value from surplus or low-grade apples the processing conditions and fruit characteristics this season introduced new technical and operational learnings.

The exercise once again emphasized that value chain development is not a linear or uniform process. Each season, location, and batch of raw material presents distinct challenges that influence output, quality, and efficiency. The Shamshi processing run highlighted how fruit maturity, handling conditions, and packaging systems collectively shape the outcome of an otherwise well-designed processing workflow.

Raw Material Characteristics and Their Influence on Processing

For this year’s processing activity, a total of 500 kilograms of apples were used for juice extraction. Unlike last year’s batch, the apples processed at Shamshi were over-ripened and had begun turning powdery in texture. Such apples are usually considered unsuitable for fresh market sales due to their reduced firmness, shorter shelf life, and lower consumer appeal. As a result, they often face a high risk of being discarded on the farm or sold at distress prices.

However, from a value chain perspective, these apples still hold significant potential. Over ripening leads to the breakdown of complex carbohydrates into simpler sugars, increasing sweetness. While this affects physical structure and juice recovery efficiency, it enhances the natural sugar concentration of the fruit, which directly influences juice quality. This batch of apples therefore presented an ideal case to examine the trade-off between juice volume and sensory quality, a critical factor in processing decisions.

Juice Extraction and Yield Observations

The juice extraction process at the HIMCO Juicing Plant resulted in a total output of 125 liters of apple juice, equivalent to approximately 250 bottles. Compared to standard expectations, the recovery rate was lower. This reduction in volume was primarily due to the powdery flesh of the apples, which caused increased retention of juice within the pomace and reduced efficiency during pressing.

Despite the lower extraction volume, the Brix value of the juice measured 19°, which is significantly higher than average for cold-pressed apple juice. This high Brix reading indicated a concentrated natural sugar content, resulting in juice that was exceptionally sweet, flavorful, and palatable, even without the addition of sugar, preservatives, or color. While the higher brix also – in exceptional circumstances lead to aerobic yeast fermentation and higher degree of browning due to Maillards reaction, the Pasteruization process of the bottles and the juice ensure that the impacts are in control. Also the fact, that we always produce a limited lot to market during winter season only.

It is only right that we eat apples in season instead of selling juice in quantities which are a marketing and supply chain challenge. The juice this year has a nice Orangish hue to it also apparent from the photographs below. This is the trade off needed to avoid adding synthetic preservatives, colors or sugars to value added products. We have also chosen not to dilute the juice with additional water, thereby providing consumers with a product close to consuming a real apple.

This outcome reinforces an important insight for agro-processing value chains: yield alone should not be the sole indicator of success. In certain contexts, especially where premium or naturally sweet products are valued, quality parameters such as Brix and taste can compensate for lower volume recovery. The Shamshi experience clearly demonstrated this dynamic.

Processing Quality and Product Integrity

Throughout the processing cycle, the juice remained completely free from swweetners, additives, preservatives, and artificial enhancements. The cold-pressed nature of the extraction ensured minimal degradation of flavor and nutritional attributes, while maintaining the authentic taste of apples. The final product was rich, naturally sweet, and well-balanced, making it highly suitable for health-conscious consumers who prefer minimally processed beverages.

From a sensory perspective, the over-ripened apples contributed positively to the final product. The sweetness was pronounced yet natural, and the juice carried a depth of flavor that would be difficult to achieve with under-ripe or standard market-grade fruit. This further supports the idea that apples rejected by conventional markets can still serve as valuable raw material in carefully designed processing chains.

Packaging Challenges and Post-Processing Losses

One of the major operational learnings from this year’s exercise was related to packaging and cap integrity. During bottling, several caps failed to seal properly, leading to leakage and subsequent loss of juice. As a result, an estimated 5 to 10 liters of juice, equivalent to approximately 10 to 15 bottles, were lost.

Although the volume lost was relatively small compared to total production, this issue underscores the importance of robust packaging systems in value chain sustainability. Losses occurring at the final stage of processing are particularly significant, as they represent the cumulative loss of all input’s raw material, labour, processing time, and energy. This experience highlighted the need for stricter quality control mechanisms, better cap selection, and improved sealing procedures, especially when working with glass bottles and liquid products.

Value Chain Insights from the Shamshi Experience

The Shamshi processing exercise offered a realistic and grounded understanding of how value chains function under non-ideal conditions. Over-ripened apples, which are often considered a liability, were successfully transformed into a high-quality juice product. At the same time, the challenges faced during extraction and packaging revealed areas where efficiency and reliability can be improved.

The experience reinforced the idea that sustainable value chains must be adaptable. They must account not only for ideal raw materials but also for variability in fruit quality, maturity, and handling conditions. When designed thoughtfully, such value chains can reduce food waste, stabilize farmer incomes, and deliver products that align with consumer demand for natural and chemical-free foods.

Pricing Methodology

The pricing mechanism for the juice was determined through a comprehensive cost-based approach that accounted for every stage of the value chain.

This included –

- The imputed cost of apples per kilogram

- Packaging materials such as bottles, local aggregation

- Transport and logistics from farm to Delhi

- Transportation to the HIMCO juicing facility in Kullu

- Processing costs, return logistics to Delhi for marketing,

- Applicable taxes, and

- A reasonable retail margin for B2B and B2C returns.

This ensured that the final price reflected true value addition rather than arbitrary market rates. A critical enabler of this process was the segregation of B and C grade apples at the farm level. While B grade apples may occasionally enter local markets, C grade produce is typically excluded due to poor visual appearance and is often diverted to low-value uses such as drying, animal feed, or is simply discarded, resulting in significant food waste and lost income potential. In this case, farmers supported the initiative by supplying these otherwise unsold apples at a lower price, packed carefully in proper boxes suitable for storage and processing. This usually allows for holding the apples for slow ripening in Cold Stores or Controlled Atmosphere chambers. Once ripened well at a Brix of 12 or more, these make for delicious juice with a good shelf life.

This collaboration allowed the produce to be channelled into juice extraction, demonstrating that despite their lower market grade, these apples generated substantially higher economic value through processing than they would have in conventional pathways. By converting B and C grade apples into a finished retail product, the exercise clearly illustrated the hidden value embedded in lower-grade produce and reinforced the importance of grading-based utilization.

Had these apples not been segregated and processed, they would almost certainly have gone to waste, highlighting the strong alignment of this model with SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), SDG 1 (No Poverty), and SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) through waste reduction, improved farmer participation, and enhanced value realization across the supply chain.

To know more about the farmers and sources of these apples see our previous article here.

Conclusion

The 2025 cold-pressed apple juice processing at the HIMCO Juicing Plant, Shamshi, served as a valuable continuation of last year’s value chain development work. While the operation encountered challenges in the form of reduced juice recovery and minor packaging losses, it successfully demonstrated the potential of over-ripened apples to produce high-Brix, naturally sweet, and high-quality juice without any additives.

This experience added depth to the understanding of post-harvest management, processing efficiency, and the delicate balance between quantity and quality in agro-processing systems. It also highlighted that true value chain development lies not in eliminating losses entirely, but in learning from them and refining systems to improve sustainability, resilience, and overall outcomes.

As value-added processing continues to play a crucial role in reducing horticultural waste and enhancing farmer returns, such practical, field-based experiences remain essential. The Shamshi exercise stands as another step toward building more inclusive, efficient, and sustainable apple value chains in Himachal Pradesh.

Here is the full value chain report for this product for future reference.