MoolyaSHIKHAR True Price Accounting

Case Study 2025–26

A Ground Level Transformation in How Farmers Understand the 'True' Price of Their Agroecological Produce - Apples through Natural Farming

For decades, apple farmers in the Himalayan belt have lived with one fundamental uncertainty –

What should be the right price for their apples at the farmgate/ Mandi?

This question has rarely been answered by the people who deserve the answer the most the farmers themselves. Traditionally, the price of a farmer’s produce has been dictated almost entirely by mandi committees and adhatis, leaving growers with very little clarity about whether the price offered to them reflects the true cost of what they grow.

The MoolyaSHIKHAR Study was created specifically to correct this imbalance. The idea is simple yet revolutionary. It answers the question –

‘What should be the True price of my produce, at the market of my choice?’

While the methodology being developed itself is crop agnostic, we tested in again this year with the Apple crop. As Apple is the main crop of Himachal Pradesh and also its economic backbone, the choice is deliberate and appropriate.

Before going further, let us provide an visual reference for our motivation to make a sincere attempt to solve this challenging problem of Price Discovery. We have seen the plight of the farmers at the Juncture of transaction with the markets. At GDT we have a saying in hindi –

खेती और व्यापार दोनों का दायरा अलग है!

Agriculture and trade have different borders.

It is the overlap of these borders that the Farmers, especially smallholders, are – almost always – at a losing end.

Here is a short and sensitive film which properly shows these junctures and the challenges which the farmers face.

Before analysing the methodology and price discovery case studies readers are encouraged to delve into aspects of Innovation for Sustainable Food Systems relevant to this case. Specifically the publication –

FAO and INRAE. 2020. Enabling sustainable food systems: Innovators’ handbook. Rome.

https://doi.org/10.4060/ca9917en

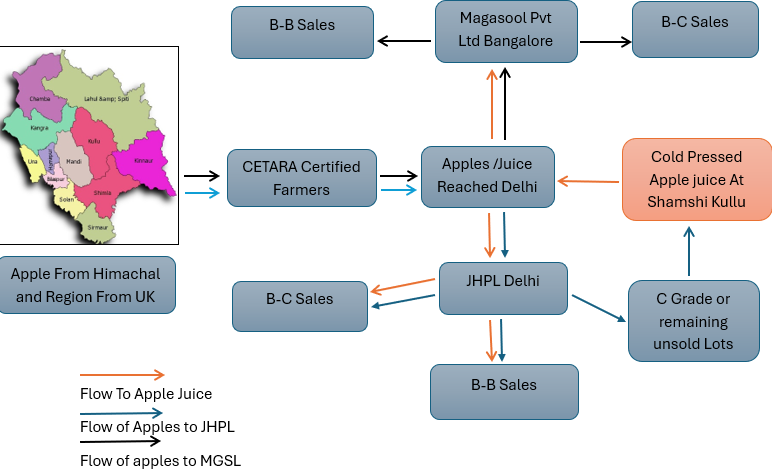

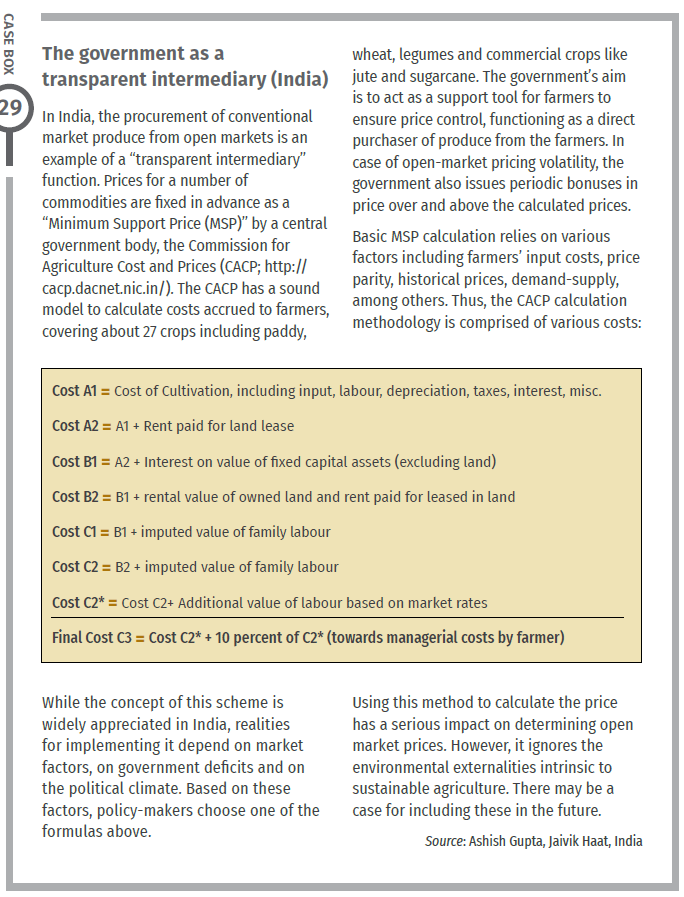

There is a distinct chapter on Right Prices for Sustainable Food Systems which is referred. For such systems there are three capitals for consideration – Social, Ecological and Economic. Corporate systems focus only on Ecomomic Capital whereas the Public Systems (MSP) combines social and economic capitals. Here we should how ecological Capital may also be encapsulated in the methodology.

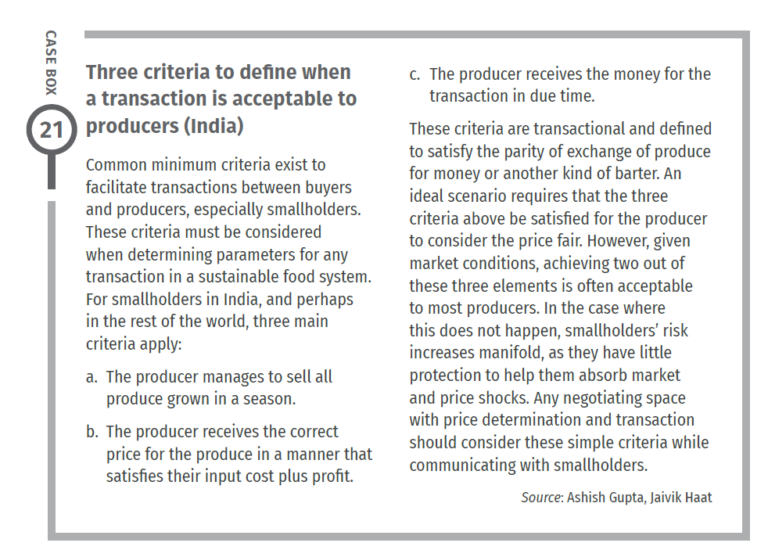

This chapter has innovative ideas and examples from across the world where prices are keeping the producers at the center. Intuitively it is only the farmer who will know the real price of cultivation since consumers and other stakeholders involved are unable to undertake the same activity as the farmer. Within the chapter is an interesting case box which provides a three criteria system for transction with producers. It is interesting that MoolyaSHIKHAR methodology enables fulfilment of – at best 3 and at average 2 – out of the 3 criteria described.

Combined with this Methodology we chose to fulfil 2 out of 3 criteria at all times and 3 out out 3 at best. In fact, with the participatory price discovery process we describe below, we take this a step further with Finding the ‘True’ Price.

This Innovative Methodology may appear basic, however, this is based upon a functional understanding not just of markets but on how Agriculture Production takes place and the transact the market – thus the core of Market Linkage for the farmers. The net returns to farmers are, at times, misunderstood as a function of price alone. Wheras it is a cross of Price and Volume ( Price x Volume ) which determines the return. Both have to be optimal for the income to be proper.

It is important that for this system to work in favor of farmers the Social enterprises function as ‘Transparent Intermediaries’ as also defined in the Innovators handbook and chapter.

The farmer must know the true value of his produce based on real, calculable cost not assumptions or third-party declarations.

Understanding the Heart of the Study: What Is ‘True’ Farmgate Price of any produce?

The MoolyaSHIKHAR methodology informs farmers how to calculate their ‘True’ price range using actual numbers. This includes:

- Cost of all inputs used during the season

- Wages paid to hired labour

- The farmer’s own labour hours, converted into monetary value

- Transportation costs incurred till the nearest market of the farmers choice

- Investments in packaging, post-harvest material, tools, and maintenance

- Consumer Participation – Net returns from the End consumers – B2B and B2C sales – Spot Price and Volume Discounts – B2B margins

- Farmer Participation – Adjustments through Supply Chain Losses and recoveries – due to Production Quality, Grading issues

- And finally, the farmer’s rightful and ‘True’ price Discovery post realisation

By putting these factors together, it shall be possible for a farmer to calculate the minimum price he should receive for his produce before sending a single kilo of produce to the market. This prevents the exploitation that stems from not knowing one’s own baseline costs. In our experience we are able to return 60-70% of the final market price back to the farmer.

Farmers rarely, if at all, undertake True Cost determination of their efforts and produce. It is also the case that there are no easy or available methodology which allows farmes – especially smallholders – to do so. They simply estimate and accept whatever the market gives to them as a price for their produce. With every passing season and historical price discovery – averages for future prediction may be drawn from the MoolyaSHIKHAR methodology. This coupled with estimates of Volume production at farmers end may also help lock procurement contracts with farmers in advance. This also offers farmers an additional benefit of being able to negogiate the best returns for the produce based on the production effort they make.

While MoolyaSHIKHAR – at first – appears to be crop agnostic, it is important to note that this methodology works very well with farmers who are in transition from Chemical to Agroecological (Natural/Organic) production. This allows for sufficient incentive for those farmers who are serious about such conversion. In our case we applied the MoolyaSHIKHAR methodology only to 2 and 3-star rated CETARA-NF farmers. This is only right since 1-star farmers may be able to fetch prices in the regular open markets/mandis, so the incentive is for those who have actually taken the effort for agroechemical elimination. Incentives such as Green/Carbon credits or Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) may also be built upon such mechanism.

These then provide greater benefits to those farmers who make the effort for Sustainability in Agriculture.

Price Discovery is a wicked problem and is also at the root cause of farmer distress in India. MoolyaSHIKHAR, as a proposed solution is, suprisingly, simple and all its need is Honesty for every stakeholder in the Agrifood system chain.

In fact, if anything, MoolyaSHIKHAR is an Innovative participatory price discovery method which involves all the actors of a food system. This also includes the end consumer. Therefore it work by institutionalising trust and providing a chance to all stakeholders to participate in ‘True’ Price Discovery.

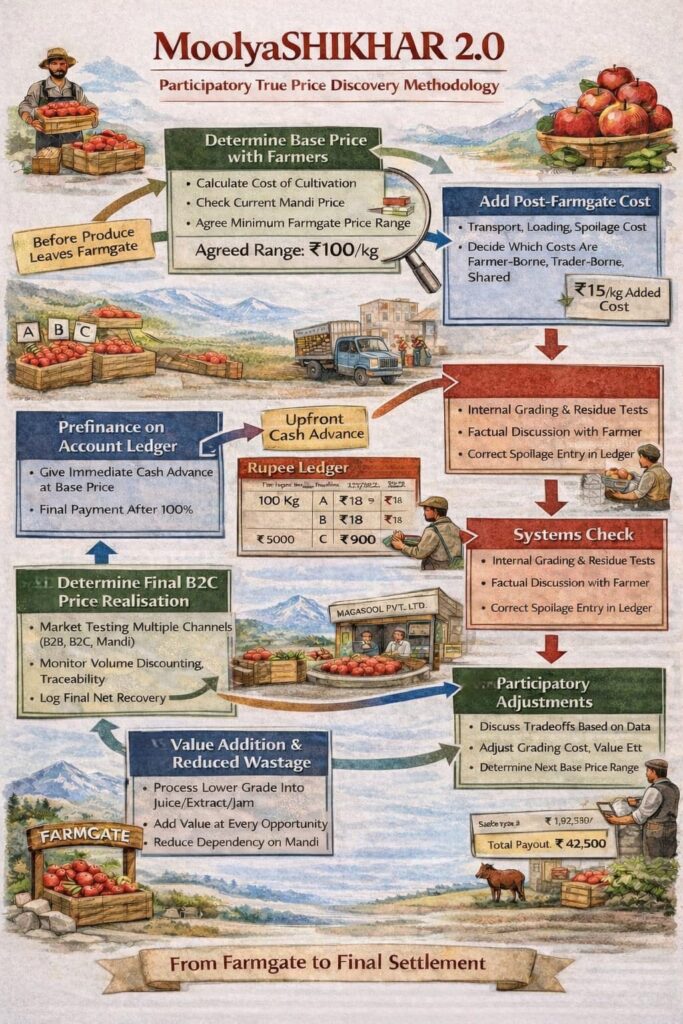

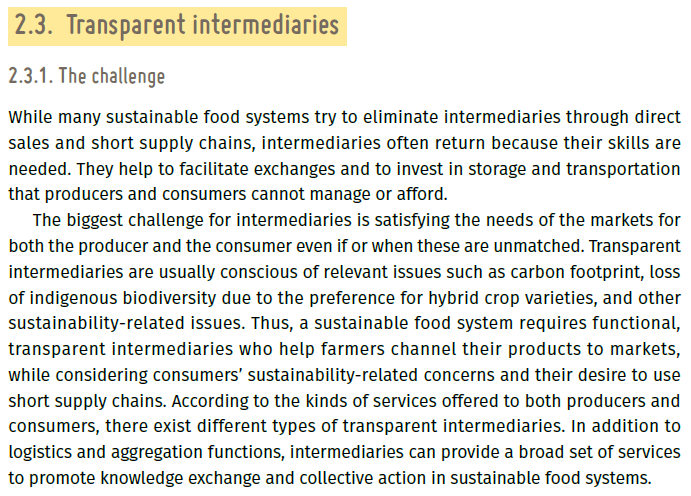

The graphics here are indicative of the overall flow of the MoolyaSHIKHAR methodology.

Methodology – From Farmgate to Final Price Discovery

The MoolyaSHIKHAR methodology is designed to bring transparency and logic into Crop Price Discovery by mapping every step of the value chain.

Instead of relying on mandi declarations or speculative rates, the study follows a cost-plus, evidence based approach.

Step-wise process –

- Farm-level grading and segregation – In this case, Apples were graded into A, B, and C categories at the source. Special focus was placed on B and C grade produce, which is usually undervalued or rejected by mandis or open auction markets. Produce grown with agroecology without chemicals, at times, do tend to have blemishes which are not considered suitable for open markets. The quality of the produce also reflects the hard work farmers put in to grow crops without chemicals.

- Base procurement price setting – The farmgate price was determined after accounting for cultivation costs, labour (including family labour), packaging, and local transport to aggregation points. This accounts for Farm-gate prices. Usually these pare with the Minimum Support Price (MSP) system of the government, however MSP is not available for the Apple crop. In future, the base price may also be calculated as ‘True Cost Accounting’ based. This amount if not realised by the farmer may be paid as Ecosystem services for farmers practicing Agroecology.

- Logistics and handling: Costs of transport to destination markets were added. This is an important cost since farmer have to often forego this consideration or take a hit on the price – if it falls in the open market/mandi – at times to a level which does not even cover the cost of logistics and handling. It is also important to note that the Mandi deducts the cost of transportation and handling from the total value paid to the farmers. However, in this case the costs are added in the MoolyaSHIKHAR methodology.

- Market testing and sales: Produce was sold through a mix of B2B, B2C, and mandi channels to capture both real and speculative price behaviour. Maximising net sales price on spot with consumers and normalizing for discounts offered on volume sales.

- Final price discovery: Gross sales were calculated, operational costs deducted, and net returns distributed to farmers proportionally.

This step-by-step flow ensured that price discovery was rooted in actual data rather than assumptions.

All aspects of Agrifood systems and stakeholder play a role in this methodology –

- Quality of Produce by the farmer

- Acceptance of quality by the consumer

- Base price set – either by Mandi or through inherent discovery or True Cost Accounting at farmgate

- Supply Chain aspects – sorting, grading, transportation, losses

- Spot price maximization

- Aspect of Ecological Production etc.

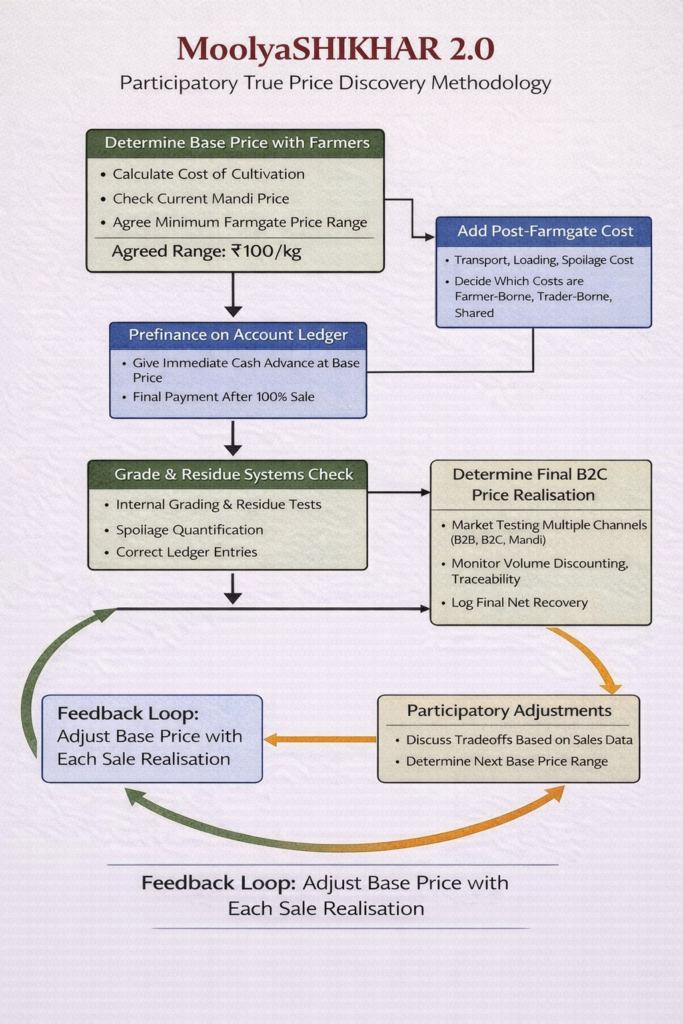

As one of the criteria of transaction in a food system is the farmers get their money on time. In the MoolyaSHIKHAR methodology the base price set with the farmer offers them an immediate Cash component at this price on production of Produce at the market of thier choice. In our case the market is at JaivikHaat in Delhi along with other social enterprises across India such as Magasool based in Banglore. Both organisation function as Transparent Intermediaries – as is also an innovation defined for Sustainable Food Systems.

In 2025, the Spiti farmers were paid this amount in parts as advance, during truck departure from Spiti and then once the produce landed in Delhi once the goods were checked. This allowed for the farmer to start realising value of their produce as soon as it departed their Farmgate. In case of farmers in general, on account ledger funds transfer is enabled, as and when the produce is sold in the market. The final price is then calculated once 100% of the produce is liquidated. These are also shared with the farmers for confirmation and then the final balance transfer are made. This final calculation then normalized by the total produce procured at farm-gate is the eventual ‘True’ price discovery of MoolyaSHIKHAR methodology.

Intuitively as this is based on the ‘Truth’ of the Agrifood system – the truth of production, supply chain and consumption – this methodology enables an insitutional trust in ‘True’ Price discovery.

Therefore all stakeholders – farmers, traders (transparent intermediaries), consumers and policymakers play a role in this price discovery.

Constant feedback loops – at base price setting, adjustment for grading or production losses and final price discovery – occur throughout the supply chain to maximise returns while minizing losses. Such Innovations do not exist iin the convential market system for price discovery.

Once these loops converge what started as the Base Price develops into the Pinnacle Price realised through participatory price discovery by all stakeholders in the Agrifood system.

It now becomes clear why the name of the methodology is MooylaSHIKHAR. The name is a lexical compound with –

Moolya (/ˈmuːljə/ – pronouced Mool-yuh) is a Sanskrit word (मूल्य) for Value or Price

SHIKHAR (/ˈʃɪkʰər/ – pronounced SHICK-her) is an acronym for ‘SuSPNF based Himalayan Innovation for Knowledge Platforms, Hi-Technology, Agroecology and Robust Marketing Networks’ – it is also the Sanskrit word (शिखर) for Peak or Pinnacle

Thus together this methodology helps determine peak value for the Farmers produce – the relative metaphor being ‘as high as the mountain can be’. This discovery of price is as close to the truth of the value as is possible in an Agrifood system. Therefore MoolyaSHIKAR is a ‘True Price Discovery’ system through Pinnacle Pricing methodology.

Regions Covered Under the Study

To verify the practicality and impact of this model, we expanded procurement significantly this year. Apples were sourced directly from farmers across:

- Chamba District

- Shimla apple belt (various altitudes)

- Mandi District

- Kinnaur (Kalpa, Sumra)

- Spiti Valley

- And certain regions of Uttarakhand

This geographical diversity allowed us to understand differences in costs, quality variations, logistics challenges, and the unique on-ground realities faced by each growing region. It also helps connect the timing and availability of produce. The regular market moves through speculative arrivals based on demand/supply or at times – hidden in plain sight – collusion!

Procurement Scale and Financial Scope

In total, we procured about 23 tons of apples from these regions enough to create a meaningful sample dataset that accurately reflects real-world conditions. The total procurement value stood at over ₹25 lakhs (over US$27000) all purchased directly from individual orchardists who are involved in natural farming practices. A visit to most of the farms was done to have a deep understanding of the practices and farmers share/ importance in this study. This volume and investment were necessary to test whether the MoolyaSHIKHAR concept stands strong across grades, varieties, markets, and regions not just in theory, but in real execution.

A Special Highlight – Only Natural Apples Procured

One of the most important decisions of this year just like last year was to procure only naturally grown apples, all of which were certified under the CETARA-NF system. This allows for the MoolyaSHIKHAR model to be applied also in specific cases e.g. it shall apply only to 2 and 3-star rated farmers. It is also important to note that the farmer should also be ready for their claims to be tested in the market. One key criteria for Agroecology to be successfull for all stakeholder in an Agrifood system is that it should not have Agro-chemical residue detected in the samples which are sold to consumers. Afterall this is also a matter of upholding trust for the consumers. It is this aspect which includes Ecological Capital within the MoolyaSHIKHAR True Price Discovery methodology – thue enabling it as an innovation which includes ‘All Capitals’ (Social, Ecological and Economic) for Sustainable Agrifood Systems.

This was done deliberately to break a long-standing myth among both growers and buyers that natural apples do not fetch good prices. Our results proved the opposite. With the right value chain and transparency, natural produce can earn premium returns, strengthen farmer trust, and attract high-paying buyers who value clean and responsibly grown food.

While the MoolyaSHIKHAR methodology is crop agnostic, the choice of Apples for this study is important since it is the most important cash crop of Himachal Pradesh. As this study allows for a larger crop transaction in a season spread across multiple farmers and locations, the choice is deliberate. However, in the past we have also applied the same methodology to various transactions with farmers who are willing to participate in developing the innovation with us. The Primary data for the same – over the years – is with our social enterprise JaivikHaat – open for study and research purpose to continue developing such innovations.

In 2025, we could not apply this Methodology to at least 2 farmers on whose produce the Residue was detected. It is important to remember, that pathways are to be found to support even these farmers instead of abandoning them. Thus the farmers were asked for adjustments in the shipment and paid a price which is comparable or more than the Mandi rate they recieved for their surplus produce in 2025. To know more about how this issue was managed along with details of the case, readers are referred to this study. This case demonstrates not only how the support system for farmers at large is possible despite challenges, but also how the CETARA-NF system works in a feedback based, participatory loop to allow for continous improvement.

Real-World Challenges: Losses, Damage & Transit Issues

Even with the strictest handling protocols, apple transportation at scale brings unavoidable losses. During the study, we encountered:

- Touching damage due to box compression

- Core rot discovered during regrading

- Powdery apples caused by micro-abrasion

- Minor bruising from long-distance transport

These lots could not be sold directly into the market. That forced us to make percentage adjustments on total volume, reducing the saleable quantity.

But here lies one of the strongest achievements of this year’s project:

Even on the adjusted, reduced volume, we ensured farmers received MORE THAN their primary invoice value.

This outcome not only reflects our commitment to fairness but also highlights the critical importance of proper packaging, careful grading, and farmer-level awareness of post-harvest practices.

Region-Wise Return Delivered to Farmers

After selling the apples across various B2B and B2C channels and after accounting for all operational expenses we arrived at clear region-wise return percentages:

Powered By EmbedPress

Powered By EmbedPress

These figures represent the share of final sales value returned to the farmers. In most regions, this is significantly higher than what growers typically receive through traditional mandis. Across all regions combined, the net return stood at 66.37% for this year’s study. Additionally, one of our B2B partners (Magasool) voluntarily contributed an extra 10% directly to farmers on the Base Purchase price, acknowledging the importance of transparency and fair compensation.

Direct Comparison With Mandi Pricing

To strengthen the study’s scientific credibility, we sold a portion of the incoming apple lots directly in the mandi, immediately upon arrival. These same lots were then tracked in the MoolyaSHIKHAR chain. This is also a strategy to determine base price. Presently alternative markets for Natural Farming produce does not exist, therefore any surplus produce of the farmer also has to sell through the Mandi. Usually, it is acceptable to the farmers if at the minimum their produce is valued at Mandi prices. Therefore in MoolyaSHIKHAR it is also possible to set this as a base price.

In future, the Actual or “True Cost Accounting” of Production for Agroecology may replace the base price setting. This shall produce a minimum and maximum range with which the farmer shall be able to negotiate a price with the market. Technology also has a role to play, where farmers can set their actual GPS location against the coordinates of the markets of their interest and the system shall enable a True Price Discovery model for them. The comparison revealed that farmers earned 30% to 35% more through our transparent system than they would have earned through mandi channels. This is a powerful indicator that the current market system severely undervalues farmer produce with the farmer bearing the majority of the loss despite being the primary producer.

Key Insight: Lower Farmgate Value Creates More Room for Higher Returns

One of the most interesting insights from this study is that regions with lower initial farmgate pricing actually gave us the most opportunity to create higher market returns.

This is because lower base value allows more flexibility to position the produce in markets where the selling price is significantly higher than the procurement price.

This insight will help farmers make important decisions in the future, especially when choosing:

- Which mandi or market they should send their produce to

- How much cost they will incur for transportation

- What expected return they should achieve from that specific route

This empowers farmers not just with a price for today, but with a strategy for all future selling seasons.

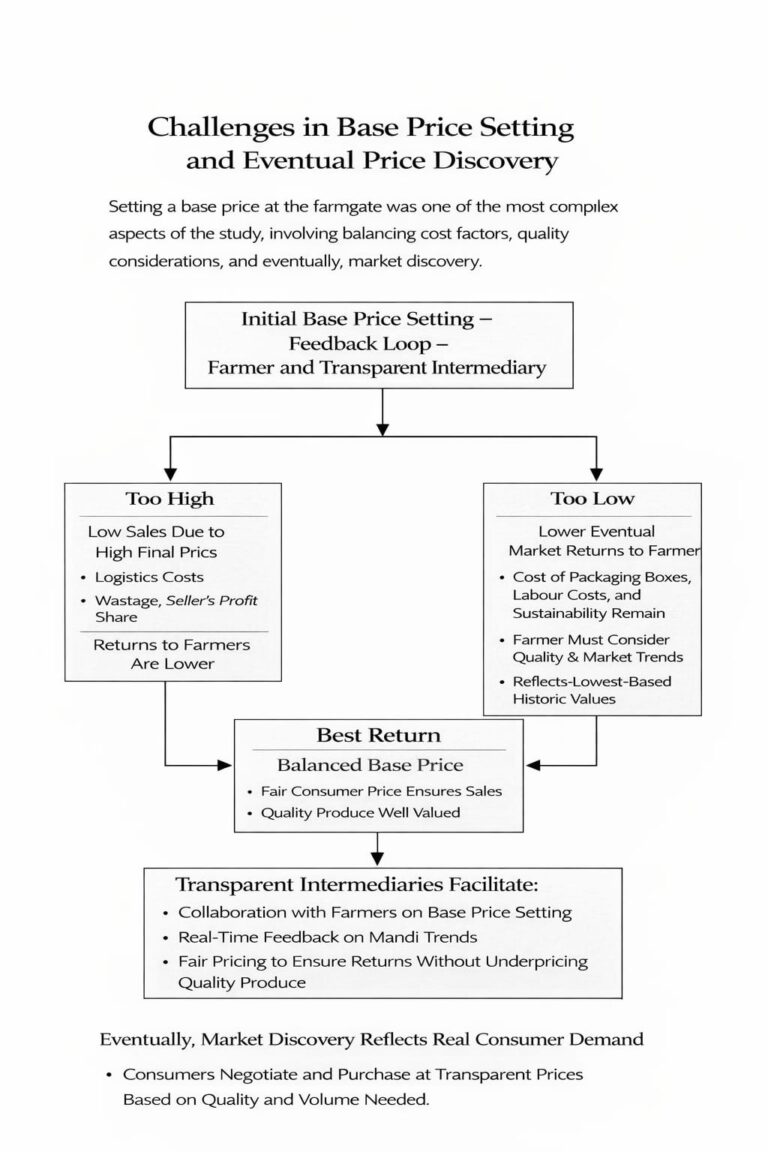

Challenges in Base Price Setting and Eventual Price Discovery

Setting a base price at the farmgate was one of the most complex aspects of the study. Key challenges included:

- Wide variation in regional costs (labour, packaging, terrain-driven logistics)

- Very low flexibility given by farmers in terms of lower price set during initial phase when helps in further return calculation.

- Absence of reliable mandi benchmarks for natural and non-A-grade produce

Price discovery evolved gradually as apples moved through different markets. Initial High price increased once real sales data from B2B buyers, retail channels, and mandis became available, allowing final prices to be far higher affecting actual demand.

In our case the base price is set as per the following considerations with the farmer –

- Mandi Prices – these are averaged across grades to arrive at a Gadh combined rate across Grades. Here the base price remains same for all grades and varieties of the crop. Specific prices for quality are discoverd through transaction with consumers.

- Historical Base prices for specific qualities of produce. E.g. Small grade Gala apples historically do not command higher prices with the consumers but Large Grade Granny smith vareity does. This level of information for suitable exchange with the farmers is possible once Social Enterprises have had experience in the market as Transparent Intermediaries.

- Past transaction with same farmers based on mutual trust. In this case they leave it to the social enterprise to work the best for them.

- Farmers own confidence – Some farmers are confident that their produce shall fetch a good price as they have grown the produce with quality.

It is important to consider that –

- If the farmer sets the base price too high ( due to high speculative Mandi price offset) and the quality is not acceptable to the consumer then the price discovery will be skewed against the favor of the farmer since Consumer shall not pick up the produce at such a high market price.

- If the farmer sets the base price too low then the possibility of maximising the market returns could be lost – therefore Social enterprises help set the base price for the farmer optimally.

- For new farmers – the Transparent Intermediaries (or social enterprise) provide an easy path to help build trust. They offer to let the farmer decide the price but provide active feedback on the current market situation and how the produce from other farmers is faring. This also helps the farmers take a call on the base price to set.

The combination of these factual transaction result in emergence of the ‘Truth’ of the exchange and thus discovery of the pinnacle price. Eventually the transaction between the consumer and producer is enabled by the Transparent Intermediary on the basis of availability of produce and its quality. If the produce is of high quality then consumers will have lesser challenge in a higher price, as compared to a low quality product attempting to demand a higher price. In each scenario the truth of the transaction coverges to the Pinnacle Price from its relative base. The truth of the transaction is thus filtered into the final price for the farmer as the highest possible they could realise from the market.

One of the key issues in India – due to which farmers are distressed and protest periodically – is related to the Systems Design of the MSP (Minimum Support Price). The MSP by itself is a suitable Social Capital realising methodology but it excludes Ecological capital. However, the systems design put tremendous pressure presently on the public exchequer not just due to the price setting but also due to the volumen procurement for public distribution.

MSP is simply a tool which internalizes Economic and Social Capitals to determine prices for fixed commodities in India. This tool has a deep impact with the farmers who periodically demand the MSP be increased and procurements by satisfied in their favor. However, the government is also limited in its capacity to procure and then liquidate the produce. Thus the markets have to play a serious role in being able to liquidate the produce from the farm gate to the consumers.

In MoolyaSHIKHAR – instead of presenting an alternative the MSP we take this further and innovate upon it. The choice of base price setting with the farmer could be any of these –

- MSP if it is available for the crop

- Farmers own cost estimate of production until farm gate

- True Cost Accounting systems – (which are yet to be developed)

- State government price setting mechanism

MSP as a system is applied as broad averages on National, State or district basis (at best) – whereas the reality of the farmer and distant to the market is diferent for each farmer. Therefore unless the ‘Truth’ of each farmers situation remains unrealised by the farmers – the root cause of the issue of net returns shall not be addressed. In MoolyaSHIKHAR we hope to remedy this root cause. It is important to note that this may not be the final solution, but it surely provides a pathway to get there in the future. More participatory innovation is needed to get this right for the future generations.

MSP as a system is almost legacy in India. It was lauched as a vehicle for supporting the Green Revolution in 1960s. The purpose was that if the farmers get a bumper harvest due to the Green Revolution systems design, then they do not face a price shock due to it. Over the years MSP underwent changes by modifications in methodology and adding number of crops for price discovery and procurement. It is also true that it has taken very long for MSP within the present Food System to enable procurement crops to a record over 106 million metric tonnes of crop 2022-23, benefitting more than 16 million farmers. However this comes at a deep cost to the exchequer of over IN₹ 2 lakh crores (over US$ 25 billion) annually. This makes it one of the highest in the world. The question is – will the exchequer continue to carry this burden for future generations as well or is there a way forward to relieve this?

However, despite its legacy of over 65 years its usage is unable to solve the root cause of the problem for farmers in India. It is then a question on how systems may be designed keeping in mind the requirements of the future. It is also important to understand mechanisms by which innovations may be developed based on the learnings of methodologies such as MSP within the systems context today. In MoolyaSHIKHAR we do plan to also include MSP as a viable mechanism to determing Base price, however, it is important that the innovation takes into account the Ecological Capital aspect to ensure that farmers who support the system with Agroecological production are the key beneficiaries of MoolyaSHIKHAR.

Impact on Farmer Decision-Making: Why This Matters Long-Term

In all of these the most important differnce in MoolyaSHIKHAR is that they must be Hyperlocal to each farmer to reflect the ‘Truth’ or reality of that farmer. Farmers should now be able to map their costs more clearly across regions and estimate their returns based on actual numbers rather than guesswork or speculative market led returns. They will know –

- The cost of getting their produce to each mandi or market location – hyperlocal to their actual farm gate costs

- Their expected earnings based on the region they choose

- The difference between selling locally, semi-locally, or to distant markets

- How much value their apples actually command based on grade and quality

This knowledge prevents blind dependence on adhatis and helps farmers negotiate or diversify markets with far more confidence.

Wastage and Volume Adjustments Offered by Farmers

During grading, transport, and re-evaluation, certain losses were unavoidable due to touching damage, powdery texture, bruising, or core rot. Instead of transferring this risk entirely to the buyer, farmers voluntarily supported the model by offering percentage-based adjustments on saleable volume, ranging from 10% to 30% depending on the lot. These adjustments played a critical role in keeping the value chain viable while maintaining fairness on both sides.

Importantly, even after applying these wastage adjustments, farmers received net returns that exceeded their original invoice values in most cases.

A Growing Vision: Year Two and Beyond

This is the second year of the MoolyaSHIKHAR initiative. Last year helped us build the foundation and test the model at a basic level.

This year, we expanded significantly larger volumes, more regions, deeper insights, and stronger validation. The success of this year shows that the model is not only effective but scalable, sustainable, and capable of transforming how farmers understand value.

Going forward, it is possible to envision that the Innovation of MoolyaSHIKHAR is integrated into a digital platform such as HimSHIKHAR to enable farmers a technological base to discover price. The app may then also be usable in the market to negotiate with the traders. In case the farmer still is unable to realise the true value, then the alternate channels or government may step in to offer the net differences to cover any potential farmer distress points.

It is possible to envision a system which taken into account

- Cost of Cultivation at farm gate – including profits – it could also be MSP calculated here but on a hyper local per farmer basis

- Cost of Access to markets – Hyperlocal per farm basis – with GPS coordinates from Farmgate to market location

- Historical realisations based on quality of produce – Based on Grades, Varieties and sorted outputs

- And other associated market linkage variables

To produce a Price Range {Minima,Maxima} which farmers may use as a guiding point to negotiate base Prices. This system may work in any scenario including farmers negotiating floor prices for auction in Mandis too.

In this case, as the Price Range is detemined over what MoolyaSHIKHAR may deliver eventually, if the farmers do not realise the prices as per this authorized range, then the government may step in and convert the difference as Payment for Ecosystem services for the farmers. It is important that this methodology is applied for those farmers who grow with Agroecological cultivation since that is the only way to always enhance and include Ecological Capital as part of this system. As an example MoolyaSHIKHAR methodology may be offered to 3-star rated CETARA-NF farmers as an incentive to continue the ecological practices. Here it is important to understand that this is not a ‘Premium’ pricing system but a Post-Transaction and discovered ‘Pinnacle Pricing’ system in which end consumers also play a part. Here, it may also be envisioned that the difference in the price which the farmer is unable to realize despite best efforts from the market – where market plays the primary role – then the difference may also be purchased as Credits (by the Government or other entities) from the farmer through production and Value/Supply Chain amortization. This way it may not be an eventual burden onto the exchequer always and all arms of commerce play a role in creating necessary cushions for the primary producer. However, it is again important to note that at first, always, the markets have to play a role and all stakeholders must exhaust their opportunity to support the farmer before these alternate paths kick in. This also allows for pressure reduction on the Governments to keep playing an endless role in supporting farmers only to see periodic protests and distress in turn.

Thus if the entire Agrifood system is unable to support the farmer, only in that case may the impact be undertaken through the public exchequer. It is also possible to imagine scenarios where Payment of Ecosystem services are enabled for 3-star farmers for whom MoolyaSHIKHAR kicks in everytime they access markets. It supports policymakers and the markets to support the farmer take decisions at every step of the food system. This methodology, then, also takes the load of the Public Exchequer to enter in the picture only if the markets fail for the farmers, this also reduces public expense to support the producers against distress.

Conclusion – Towards a Future of Transparent Farmer Empowerment

The 2024–25 MoolyaSHIKHAR Study is not just a pricing experiment; it is an effort to rebuild a system where value flows back to the farmer.

By giving growers clarity about their own farmgate price, exposing the gaps in mandi-based systems, and demonstrating that natural apples can fetch premium prices, this study is slowly reshaping the Himalayan apple economy.

With each year, our understanding grows deeper, our data becomes richer, and our commitment to farmer-centric pricing becomes stronger. The journey is long, but every step is bringing us closer to a marketplace where farmers finally know and receive the true worth of their hard work at the Pinnacle of the journey from farm to plate.

MoolyaSHIKHAR conceptualised and this article edited by Gupta-jee