Thinking Regeneration - How the journey began

This article did not begin as a planned piece of writing, but as a response to a call. Earlier this year, the World Design Organization (WDO) invited submissions for the Design for Planet 2025 conference. The theme urged designers, researchers, and practitioners to reflect on the pressing environmental and social crises of our time, and to imagine futures that move us beyond extractive systems.We realized that while the term sustainability is everywhere today, the language of regeneration was unfamiliar to us, inviting us into an unknown space, one that challenged design to be rethought through both ecological and cultural lenses. Our submission to WDO was not accepted, but the process of writing it left us with more questions than answers. This article is an attempt to share those reflections and continue the conversation.

At first, regeneration appeared to be the natural progression after sustainability—another stage in design discourse. But as the exploration deepened, it became clear that regeneration is not simply a framework or a trend to be adopted; it is a way of thinking and living. It shifts the focus from “minimizing harm” to “enabling renewal,” asking whether design can contribute to systems that restore, repair, and strengthen rather than simply preserve.

This perspective calls for moving beyond sustainability checklists and beginning to view design as inherently relational: tied to people, communities, and ecosystems. Regeneration positions design not as intervention alone, but as participation in cycles that already exist.

Everyday Knowledge as Regenerative Practice

This is not an unfamiliar idea in the Indian context. Regenerative ways of living have long existed here, though rarely labeled as such. Practices like reusing household textiles, repairing tools, or sustaining community-based sharing systems all embody principles of renewal. They are grounded in interdependence and continuity.

Yet, many of these everyday systems are gradually disappearing under the pressures of industrialization and commercialization, where efficiency and uniformity are valued over resilience and adaptability. What is lost is not only material frugality but also a cultural orientation toward repair, respect, and interdependence.

The question, then, is what can be learned from these practices before they vanish? And how might they be acknowledged not only as heritage but also as frameworks for regenerative futures? To begin addressing this, three case studies were examined—each drawn from lived experiences and observations.

Case Study 1 - Kantha Embroidery – Losing the roots of a regenerative craft

Kantha embroidery, practiced in Bengal, exemplifies regeneration through textile reuse. Worn-out saris are layered and stitched into quilts, extending the life of materials while embedding them with new narratives. Each Kantha carries traces of continuity—of family histories, care, and resourcefulness.

From a design perspective, Kantha demonstrates how repair itself can become a form of creativity, where renewal is both functional and aesthetic. However, as Kantha entered global markets, its symbolic and cultural meanings were often stripped away. What was once a domestic and community practice became commodified as a fashion product.

This shift highlights the risk of divorcing regenerative practices from their social and cultural contexts. Without acknowledging the embedded values, such traditions risk being reduced to surface aesthetics under the banner of “sustainability.”

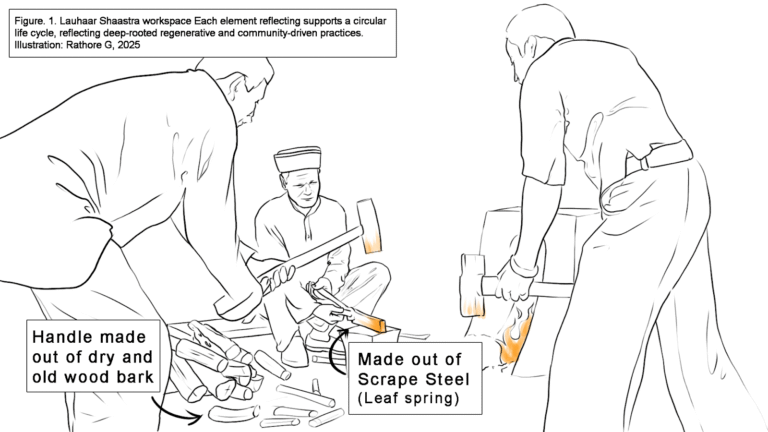

Case Study 2 - Lauhaar Shaastra - Craft as Knowledge and not just skill

Lauhaar Shaastra, preserved through the work of Gram Disha Trust, documents the indigenous blacksmithing knowledge of Himalayan communities. Lauhaars (blacksmiths) traditionally created tools, architectural elements, and ritual objects through locally rooted expertise that integrated metallurgy, forest cycles, and community interdependence. Their work was sustained through jajmaani—systems of social and economic exchange with farmers and stonemasons.

This ecosystem represented more than material production; it was a knowledge framework in which craft, ecology, and society were inseparable. Industrial manufacturing, however, disrupted these networks. Cheap, mass-produced tools displaced artisanal work, and with them, a worldview that emphasized respect for material and resource cycles.

Lauhaar Shaastra illustrates how material ethics and intentionality can be central to design practice. Reviving such knowledge does not mean romanticizing the past, but rather rethinking how traditional frameworks of responsibility and reciprocity might inform contemporary regenerative design.

Case Study 3 - Hornbill Festival – Tourism that heals or tourism that takes?

The Hornbill Festival in Nagaland provides another lens to view regeneration—this time through tourism. Positioned as a cultural revival and a platform for economic opportunity, the festival showcases indigenous music, dance, and crafts, generating visibility and pride for local communities. It reflects the potential of regenerative tourism to serve as a bridge between cultures and nature, supporting livelihoods while celebrating heritage.

Yet, the festival also reveals tensions. As an increase in larger numbers of visitors, cultural performances risk being reframed for external consumption rather than community continuity and celebration. The very practices that were meant to be revitalized are becoming staged, raising concerns of authenticity and long-term impact.

This case prompts a critical question: when does regenerative tourism risk sliding into cultural commodification? It reflects how such initiatives labeled “regenerative” can end up replicating extractive systems if not managed properly.

The Reflections

Across these stories, a pattern emerges: indigenous knowledge holds regenerative wisdom that has enabled communities to live in sync with their environment for centuries. Yet, when such practices are displaced from their contexts, they risk becoming symbols rather than living systems, marketed, commodified, and stripped of their grounding.

These reflections suggest that regeneration is not a futuristic idea but one already embedded in traditions, crafts, and cultural practices. At the same time, they highlight how fragile these systems become under industrial, economic, and cultural pressures. Recognizing this duality of possibility and caution remains essential if regenerative design is to move beyond rhetoric.

Perhaps the more critical question is whether design can create space for communities and ecosystems to thrive together. Regeneration, then, is less a trend than a worldview: one that demands humility, reciprocity, and attention to roots, ecological and cultural.

We do not want to end with answers, because the idea of regeneration isn’t a box to tick off but an ongoing conversation. It is less about definitions and more about a way of relating—to soil, to craft, to culture, to each other. What remains urgent is the need to recognize that these roots already exist around us, and they are fragile. Whether regeneration becomes another label or a lived practice depends on how carefully we choose to engage with them.