Earth Building Systems - Himachal Pradesh

Back To The Sustainable Future

What is Sustainability in Building Systems and Architecture? This question was asked a decade ago before this journey started. The answers lay in Villages of India, going back to tradition with a modern outlook.

Around 2014, while sitting in a guest lecture at CEPT University, Ahmedabad listening to a well known senior architect speak about the utter lack of sensitivity of modern architects in understanding sustainable building systems the mood turned sombre. At the end of the lecture, the floor was opened for questions. At the time I was looking for architects and eminent persons who may be looked up as mentors for the upcoming earth building system in the Pangna Valley of Himachal Pradesh. I asked

What can agriculture learn from modern Architecture?

The senior architect paused to think about the question and said –

I do not think agriculture can learn anything from architecture, however the reverse is true.

Today, I know what he meant, but there are hardly any architects worth their salt, who are ready to walk this line – in my experience thus far.

The villages of India used to be learning centers of the world. They still are, just that the world turned its face in another direction. Himachal Pradesh has a rich tradition of building systems design called Kath-Kohni which literally translates to Wood-corner. Then there is Matkaanda or rammed earth. Adobe bricks and Bamboo along with timber are used in different parts of the state. A summarised understanding shall be to work with whatever ‘Earth Materials’ are available in one’s radius, suitable to bring to the site within One Day’s effort – morning to evening. This is also inline with all species on the planet who function in exactly this rhythm of nature – Save the Humans! An ant, a bird, a cow – all create abodes in nature with manageable distances, save humans! Think about it.

Visitors to Himachal Pradesh romanticise about the old temple structure and wonder how we can ‘learn from our ancestors’. In my mind the constant question was – What can we leave for the next generation, improved upon what we got from our ancestors?

Structures of such kind exist in villages even today. Traditionally, Late Ravindra Sharma ‘Guruji’ – a renowned master craftsperson and vernacular historian – used to say – that a habitat in the village has 5 lakshan or characteristics –

- प्रकृति से प्रेम करवाए (Prakriti se prem karwaye) – Inculcates love for nature – is made of materials which are closer to nature even in end of life of the structure.

- आर्थिक रूप से सहायक हो (Arthik Roop Se Sahayak ho) – Helpful in the generation of wealth or continuously lowered the expense. Where one’s labour is the greatest wealth.

- आयरोग्य के लिए श्रेष्ठ, जहां पैर गरम पेट नरम और सर ठंड रहे (Arogya ke Lie Sreshth ho, Jahan Paon Garam, Pet Naram aur Sar Thanda rahe) – Is best for one’s health, where the feet remain warm, stomach remains soft and head remains cool. Thus the space and materials used are such.

- जो सामाजिक बनाए (Jo Samajik banaye) – which allows one to remain socially interactive, which is why village houses do not have boundary walls, they just flow from one courtyard to another.

- आध्यात्मिक दिशा में ले जाने वाला हो (Adhyatmik Disha mein le jane wala ho) – Leads one towards Spiritual goals and achievement.

Which habitat in the city, anywhere in the world are all these 5 characters met? Is it met with traditional village habitats in India?

Clearly the high rise residences fail in 5 out 5 parameters of modern living, or perhaps the characterisation of ancient times is irrelevant now? Not even worth learning from a sustainability perspective? Or to be sustainable in the future, we have to deeply look at the past and modernise its context.

These questions are not merely rhetorical, they are philosophical churnings, which beg action to reveal answers. Now, after over a decade of engagement with the village community, the answers are crystal clear. What the world talks about Sustainability in Building systems – is not what it is!

September 2012 Onwards

Land Acquired by to develop a Eco-Socially relevant space with smallholder in Himachal Pradesh. 4.45 Bighas ( just under 1 Acre ) of Riverside Terraced Land. My ancestral family being from Himachal Pradesh, with lands in adjoining districts, it was a conscious choice to go and work for the state where our family is originally from.

In selecting the land the following were under consideration

- Relevant as Smallholder farmer

- Uncultivated/Abandoned farm for over 3-4 years

- Opportunity to startup a social experiment/experience in conjunction with Jaivik Haat which was founded in 2009

- Safe space for Children to learn while have fun i.e. it should be simple

- Support by Friends/network/family in nearby areas/district/state – special acknowledgement here to friends Vikram, Rajni Rawat and Family (Kalasan Nursery Farm) who was instrumental in connecting with Farmer and coordinating land access

- Natural Resources Available – Stones, Trees, Water (River fed source), Kulh (traditional arterial irrigation channel), Within Village space for community interaction, Buffer zone with neighboring farm to support organic agriculture

- Needs of the farmer who was selling the land was respected. The farmer selling the land needed funds for higher education of their child – Engineering.

Thus with a foresight in Learning, reverence and mad risk, this task was undertaken.

Back in 2012 a general concept was drawn which started with the Naming of the project or program. At the time, it was clear that the concept should draw from Social Impact, Ecological Change relative to Farming and craft. At the same time all work done should be easily cognized by children. Only then will the work be deemed sustainable, if all of this is carried onto the next generation. Therefore, the terms came out to be Krishi, Kala and Bal. Historically, it was also thought to name the place starting with Gupta-jee’s late Grandfathers ( Maternal and Paternal), they were named Balak and Puran, respectively OR in giving with the Gandhian thought it could also be called ‘Swaraj‘. As it was to develop as a space which helps develop one’s spirituality the word ‘Ashram’ was added.

The land survey was also an interesting process. As there was no architect (or no one was interested!!) in supporting the process, I referred to the closest person he knew to explain the process. With no background in Civil works, he was recommended to use common sense and take up a paper sketch with his ‘feet’. Literally then, with an approximate Step of the legs of 3′, I mapped the terrace starting from point 0′ downslope to the river. The paper drawing was then mapped onto a Google Maps satellite plot by Sachin Sachar – a designer par excellence – to map the approximate plot plan layout as below. Thus it all started with the basics of how regular village folk manage their lives – without Architects, civil engineers or finance, based solely on the strength of one’s own wit and labour. Thrown in were a gratuitous dollop of freely available Technology, which at that time was pretty High-Tech for a rural village in India.

Early realisation was (perhaps around 2008), that if a sustainable project is to be embarked upon, then clearly Urbanised Industrialisation could not be anchored to develop alternatives. Jaivik Haat was already up and running since 2008. My forays in Himachal Pradesh with Kalasan Nursery Farm (KNF), were also influencing these decisions. KNF has always been an interesting place to visit over these years. It has also been a source of discussion and debate on the limits of Sustainable Living for rural folk. Despite all the challenges, KNF has retained its Rural flavour and cultural idiom while merging itself into the Natural Rural Landscape while inculcating modernism too. This was inspiration enough to challenge in developing a space which could be proof (to oneself) that alternatives were possible indeed.

Once the land was purchased the next logical step was to build some sort of shelter or habitat. However, it was clear that the center would be dedicated to Rural ideas and Nature. It was not to be, in hindsight, a personal space for one’s family but for the Rural Community at large.

April 2013 onwards

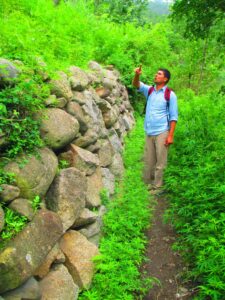

In keeping with rural aspects, ecological considerations and available resources – human and material – it was decided early on that Earth Building shall be the first choice of material. Locally sourced material was available to see, but it was not immediately clear how it could be acquired and used. For human craft, it was fascinating to see stonemasons make complex decisions such as choosing the right boulder, the axis of hammering, ergonomics, efficiency and the economics of net returns.

It was providence that the Village Baag, where Gram Disha Trust operates from was inhabited by Stone Masons. A few families still had houses which they constructed themselves over the years. This is the first 5 Tonne (approx) boulder , on the farm, which was shattered by the Masons in a span of 3 hours of hard labour using iron chisels and tools of the trade, from early morning till about 8am. It is this boulder which transformed into the Gram Bhawan of today.

The beginning is always exciting and for a constant learner – with an open mind to seek from the rural – the observed knowledge gained is an eye opener. Once it was clear that the Boulder shall be the source of material, I decided to dive in and work with the stonemasons of the Pangna Valley.

The first step was a deep experience into interdependence among rural communities. I had heard about the caste system, complex rural interpersonal dynamics and much about the negative connotations that these carried. I had my own urbanised burden of a city-dweller to surpass in the mind – which was easy as I was keen to observe and learn. The least I could do was document the process. Which I did! While I kept a notebook and wrote in Hindi, the fact that money was involved in the process evolved into Accounts and Bookkeeping. Nothing could prepare me for the depth of documentation needed for precisely mapping rural processes.

Given the lack of technology at the time, absence of knowhow, I decided to do what Rural Folk do – but with an ‘educated’ method. I had a fair idea on how to keep accounts – given that JaivikHaat was up and running for 5 years now. From the stationary I bought books for maintaining Ledger and Cash transactions. I was overwhelmed very soon with the amount of Information to capture.

It was clear that since the change was warranted by myself first, it meant having to bear the cost of it all – time, money and effort! Though there was hope that the community will, over time self engage, this did occur only sporadically over the years

Till date I have the notes and accounts but these are still to be consolidated in terms of knowledge base and total costs. Perhaps I am awaiting a learner who can take these up and document them while learning about this transformative process.

A very interesting social aspect emerged at the very beginning of the work with the stonemasons. The first port of call by the masons was to the local Blacksmith. This is also true for all craftspersons such as farmers as well. The reason is simple, Stone Masons need hard iron tools to work with – Chisels, hammers and such and this is provided by the Blacksmiths.

Thus there are pre-ordained social dependencies between craft communities. The caste system is quite misunderstood in general understanding, with negative connotations, however there is a deeper socio-economic structure and dependence between various communities of the rural Himalayas. I remember walking up mountain slopes with the stonemasons to visit ‘their’ blacksmith to make the tools in his kiln. Even the iron for the tools had to be procured through scrap.

This was my first experience in working with inter-communities and observing their actions and outputs. These aspects have now been covered well with the advent of the ‘Lauhaar Shaastra – A treatise of Himalayan Blacksmithry’ which readers are highly recommended to refer to understand the depth of these relational aspects. It is a real eye opener for those who wish to understand the reality of intercommunity interplay – apart from the connotations of the caste system in India.

It is quite an experience in working with stone masons in our valley, and specifically our village. It was decided to dive head in, without knowing head or tail about it. The idea was for an ‘educated’ and foreign visited person – how hard can it be? How wrong was this ego, since most of the stone masons are unlettered men. Some have not even completed fifth grade education in life. In fact the Raj Mistry who worked on Gram Bhawan, was illiterate, but managed to build the entire structure – and educated his children to become teachers and engineers.

The stonemasons have a fascinating sense of measure, ergonomics, economics and simplicity. The unit measure of stone of approximately 9″x6″x4″ is called one Tukda or piece. The rate of each tukda is set by the stone mason, all other stones are multiple of a tukda called – Kohni (cornerstone) and Bandh (through stone). Kohni’s are used to layer corners of the building and Bandhs are interlock stones during layering. At the time, there was confidence among the local masons, that they could build 2 storey buildings with this material, which was lying right there on the site. The valley had many examples of dry stone masonry, therefore the material was within the ideas of sustainability – carbon miles and local craft. Therefore it was clear that this shall be the raw material of choice.

It is not unusual, in the rural areas for the material to come first and the design later. This aspect of rural craft is not for the utter lack of planning, but by creating a lived experience of engaging with ones craft. This does not condone planning in and by itself, it is just that unlettered craftspersons are also engineers in their own right. Traditional knowledge requires one to work within own means and efforts, a deep aspect which modern education forgoes for its pupils. If a student does not pressure themselves to perform against peers or compete themselves out of social standards, they are considered failures. The latter has turned into an unsustainable effort of existence as we now know and debate. Meanwhile, the raw material for the building was in place, the architecture drawing was to come much later. This is precisely how the progress happened on site, for there was hardly an architect worth their salt who was willing to work for rural development such as this! That happened much later. Thus bringing forth the question – what is ‘sustainable’ in construction materials? Rocks and stones near the site or Industrial cement, steel and bricks from hundred of kilometers away? The question does appear counter-intuitive, does it not?

Stone masons are efficient in their works. They know how to identify the ‘vein’ of the Stone. Once identified they are able to extract output in an efficient binary or quaternary manner. There are two main chisels at play here – the Long 9″ one ‘Taaki‘ and short 4″ one ‘Addoo‘. The Taaki is used to hammer holes in the stone to place the Adoo, which is then used to sledgehammer or ‘Ghann’ into even stone blocks. The process appears intuitive and simple, but it is far from it. It requires real skill to hammer the Taaki while avoiding looking at it lest the grit flies into one’s eyes, and chatting away with fellow masons or labour. The stone masons are so skilled that they have a ‘Bidi’( Small Indian cigar ) held at the edge of their lips talking away with their fellow workers, smoking puffs of Bidi simultaneously hammering away efficiently to create perfect stone holds for the Aadoo.

Once the sufficient number of holds have been created and the Aadoo placed, a quick forceful sledgehammer is brought down with just the perfect effort to smash the rock into the pieces of choice.

Upon observing I found this to be ‘too easy’, but hurt hands using the Taaki and a dangerous handling of the Sledgehammer sent the Aadoo flying out of its hold worrying other workers. I only found it the hard way that this skill is acquired by working with the stonemasons. To an economist it may appear to be inefficient to use manual labour, but it is easy to forgo sustainability as a tradeoff. Consider that a pneumatic drill may result in ‘quicker’ material availability, but it is expensive to use and maintain. Then there is a constant community engagement between the blacksmith and masons, which is forgotten in case of Factory based commercial purchases.

It also requires masons to forgo traditional skills which they can easily pass on from one generation to the next. It is this skill which is ‘true to type’.

Machines have a use in modern society but they come at a cost and complexity which is easily forgotten conclusively. What happens when there is no electricity or expensive fuel? There are no mechanics to repair broken equipment, it is only then one realises the importance of practicing and retaining manual labour.

A factory making steel tools may make it convenient for workers in today’s time, but the unsustainable nature of businesses and industrial setup, will remain at loggerheads with nature, when compared with community based ‘slow’ engagements. The speed and scale in which rural areas still exist is more in pace with Natural Processes than that of Urbanised modes.

The journey for a lay-educated Urban chap is actually quite interesting and adventurous, especially if there is a deep sense not to cut any corners or corrupt one’s efforts while doing so. The result is learning of a different kind like –

- Does the Government permit mining of rocks? Well the law states that if the land sale deed indicates that all the resources and material – trees, rocks, plants and such – are the property of the owner. So one can use the Material available on one’s own land.

- Can anyone go to the forest and cut trees or natural biomass to build one’s house? Yes and No. How? Well if one were to cut protected Pine timber, it will be allowed only if permitted by the forest department. However, collecting fallen twigs, Roxburghi pine spindles is ok – as it prevents forest fires. The state gives rights to forest or near forest dwelling people for this. Periodically the state also enables ‘Timber Distribution’ or as locals call it ‘Tee-Dee’, where the forest department cuts and sells ‘sustainable’ forest timber to residents for personal use.

- How does one ‘choose’ land? What are the characteristics to observe, what is the measure of land? How much is too big for a smallholder to manage? This led to discovery of the revenue system in different parts of Himachal Pradesh, which itself has a fascinating history.

- Can anyone go to the mountain side and get lime for plaster and house building? No, this is permitted by the government only to Large Cement factories through complex Contractual and Legal arrangements. It is outside the scope of a common citizen of the state to get this natural resource. There is however, the traditional rat-hole process of getting a soft natural Lime in certain hills called – Makaul. Older masons swear by the smoothness of this material, which is now illegal to mine out of the mountain side.

The basic law to read up on owning agricultural land in Himachal Pradesh is the Himachal Pradesh Tenancy and Land Reforms Act of 1972 with The Himachal Pradesh Tenancy And Land Reforms Rules, 1975. It is pretty much the same over time with laws and rules modified till present. The land revenue of a state is well worth learning about, as it also represents the historical and genealogical diversity of one’s own people. Interestingly the history of Land Revenue held at abeyance to date, which even the British did not choose to modify, was from the time of King Akbar and codified for the Lands of Punjab by Raja Todamal for managing taxation revenue, and much much more! Apart from present English equivalent terms the legalese still is worded in Farsi, which was also the lingua franca of the region for over 300 years. The basic document happens to be the Jamabandi, issued from the local Revnue office or Tehsil.

It is then an interesting experience, not just of the social effort in setting up such a system, but also connecting with one’s ancestral roots. In trying to get the revenue papers running around multiple districts of Himachal Pradesh – mainly Shimla and Mandi – from where our family history belongs, I was able to retrace our family tree to over 7 generations, through the Revenue record called ‘Shajra Nasb‘ which is pedigree or lineage table. This history was almost lost within our family with most of our extended family, having moved to cities like Delhi, had all but forgotten. Once the land revenue revealed this historical aspect, it was out of sheer curiosity that – during the demise of one of the family member – this was double checked with the Traditional Genealogical records of ‘Sanatan Bahi‘ in North India at Haridwar. There was an exact match in the family tree at both places. More about family history came to light about where ‘our people’ were from, but that is perhaps a story for another time. Here the land records show this aspect for the context at both Himachal Pradesh and Haridwar.

July 2013 Onwards

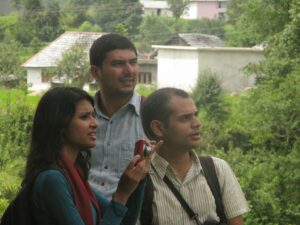

Now that the land was bought, it was a urban thought to enable a visit by Architects, Building systems experts and Designers to Village Pangna – Deliberations of what is possible with the Land. Sachin Sachar, Suresh Vaidyarajan, Pankaj Khanna, Anshu Ahuja and Rita John visited Pangna with ‘Gupta-jee’. The visit resulted in this detailed Walkthrough report which also had the nuances of the vernacular architecture and design idiom of the Pangna and Karsog Valley. This document was formative to what Gram Bhawan is today.

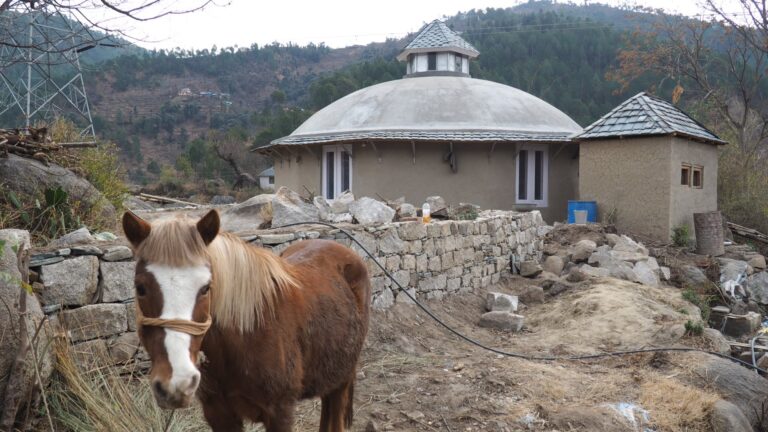

Suresh Vaidyarajan, a senior architect and SPA Alumni, went on to become the design source for Gram Bhawan as it stands today. Those who have visited Gram Bhawan know that it is a Dodecahedron ( 12-walled building ) with a Vault roof. It gives the Gram Bhawan its distinct Stupa shape. Pankaj Khanna played a role in setting up the Foundation measurement and the rest as they say, is history.

The construction itself was a unique effort, as there is no such equivalent anywhere in Himachal Pradesh. The spatial idiom of Gram Bhawan is that of Space-Time. With the 12-corners representing the Pahr, time constructed of Indian ethos and the dome/vault representing space. This aspect was covered by vernacular media in Himachal Pradesh in 2024.

The sustainability challenge ( as requirements ), for all the architectural and building systems experts was this –

- Use of Local Materials and craftsperson only – within a 20km radius of the site

- Low/No Budget availability – as is the case with common village folk

- Plenty of self labour and effort available – not just for the Jajmaan but also the Kamin (refer Lauhaar Shaastra for details on this)

- Place to stay and eat at one site – humble village life – may have to fetch water from the river even to go to the toilet!

- Modern Design is a must, but should work with the above requirements within the Rural Idiom

- No usage of cement or concrete

It did appear to be a challenge which experienced architects could undertake. However, this was an assumption which was challenged early on the project. Each architect and Building designer have their own preferences and materials to work with. Getting to a fine tuning with an architect or designer is, by itself, of an extraordinary effort. Egos, technical limitations, lack of interest and funds needed for the engagement are barriers in themselves. Therefore, in my mind, space had to be created for all these emotive aspects in addition to technical deliberations.

Most architects back out at the sight of such a challenge, others just are unable to make rent and pay bills. For a common village folk, such an idea of hiring an architect is non-existent. Then what is the purpose of Architecture for Rural Life? Is the entire strength and information ( knowledge ) of modern times a failed effort in sustainability? Do such technical minds actually exist? Such were the questions that were faced when interacting in this domain.

Over time, Suresh Vaidyarajan preferred to design a 8 cornered structure, however, with feedback from the site on the span, orientation and availability of the plot, it was modified to a 12 sided Dodecahedron. This is the section and plan of the structure. While the walls and materials matched up, it was still unclear how the Roof shall shape up. Clearly the span was large and the materials available locally may be insufficient for this span. Nonetheless, it was a determined effort to find a solution which is not just sustainable but also appropriate to local craft capacity, costs and ease of availability.

Little did one realise, just this effort will take over 2 years to resolve and the structure shall be roofless until then. The choice of architect and design influences all such decisions. Upon discussing with other architects who had experience in working with funded rural projects, the recommendation was not to start with architects in a project and rely on local craft inputs for the formative structures on a land.

August 2013 Onwards

I registered for a course on Earth Building systems and travelled to Ladakh SECMOL to learn more about Earth Building systems. The idea also was to travel to other parts of Himalayas and observe the Rural Earth building methodologies. Also to seek opportunities and collaborations with like minded people in this domain who understand sustainability and were willing to collaborate in Himachal Pradesh. In hindsight it was an incorrect assumption or expectation to carry. The result was a deeper enquiry into what Sustainability is in and of itself for the people who claim it!

The course itself was hands-on with theory, practicals and the experience of staying at Ladakh. The barren landscape was surreal and the company was endearing. Evenings spent playing guitar and singing. The one off cooking in the community kitchen was enjoyable. The earth building taught at SECMOL at the time was highly specific to the material and resources available in and around Leh. While aspects of architecture, design and effort were interesting, it was clear by the end of the course that the knowledge gained would not be much help in Pangna specifically.

The reason mainly was that the climatic condition ( Ladakh is Dry and Himachal is high rainfall), material resources available for use (Ladakh has Adobes, whereas we had stones), craft and technical resources ( Ladakh had highly educated and trained engineers and architects, who were not interested in working in Rural Himachal Pradesh at our area – in Himachal we had nothing of that sort and could not afford these expensive resource persons) – all in all – the trip was educational but could not be used to leverage any collaborations for our area in Himachal.

There was a strange endearment, bordering a fetish, for a French Organization called CRAtere , where the founder of SECMOL Sonam Wangchuk had trained.

It did not help one bit, that an organisation sitting in France would bring solutions to rural areas in Himachal Pradesh, and thus the course ended for me with a question –

If CRAtere is such a fantastic organisation as we were taught, then it must have built and created many such structures as in Ladakh, all over India or other Global South Countries, yes?

The reply was No!

To which I departed by saying that one CRAtere is not enough for India or the world, we need 100s of such institutions all around, since the biggest learning for me at SECMOL is that I cannot apply any of this knowledge to my location in Himachal Pradesh.

So SECMOL was good for the course money’s worth of information on Earth Building, useful in the context of Ladakh. The course was brilliantly designed to have people pay for it to learn and in the process end up building a Toilet Structure for the institution, and feel good about the process. Now this may have been suitable to an urban minded person looking for an exciting vacation, but my objective was not useful for the purpose of building in Himachal Pradesh. This institutional setup was not what I expected to learn or seek inspiration from.

I travelled across from Leh to Sham region, then onwards to Zanskar up to Phuktar Gompa observing the historical and local building designs, materials used and habitats of common folk – all built without the aid of any architect or engineer. It was an inspiration to be able to observe and recognise these aspects which were hidden to the eye or ignored by an Urban mind. The photos above speak for themselves about the experience.

Rightly so, as expected, no help came from any quarter across India, despite visiting and speaking to Architects, experts in premier institutions such as CEPT, SPA, Hunnarshala and Sambhavna. This was enough of an experience for me to know that there were very many Rural pockets all around India, where there is a deep need for expertise which was not available, absent or uninterested. Eventually the size of the problem was too big for all put together to solve. Since none of the national institutions put together could support the effort, localised solutions had to emerge, there was no choice. The solution to the problem emerged through this enquiry.

It was also valuable since all the places I visited there was a continuous discourse on sustainability, the need to engage and learn from the Rural Craft Idiom, importance of being learning with nature and such. However, not one person would actually engaged at Pangna valley. It was this feeling which I understood as the helplessness of Rural Folk, who bear the burden of change for Sustainability but receive no support from the people who are the main cause of Climate Change – educated Urban morass – who wish to ‘See the change’ but cannot ‘Be the change’.

A decade ago, even the well meaning architects were beset with the economic situation, where no one was willing to collaborate in this process – unless the ‘price was right’. Incessant benchmarking Rural Economics at the altar or Urban Consumerism has taken over all such institutions which preach otherwise – this has been my experience thus far. There may be Individuals and Organisations in future, I hope, worth collaborating with but so far I have not come across a single one.

The Gandhian Talisman rings hollow on most such places, which end up becoming outliers instead of engaging with the community around it.

Clearly, this was not the intent at the Pangna Valley, where the very purpose was building with a community engagement. These aspects became a learning experience which today are much clearer in approach than they were a decade ago.

It was this experience which led to all the Earth Building interventions in Pangna Valley till date. The core being to engage, revive and persevere local knowledge on earth building systems to sustain its craft. To me this localisation is at the core of Sustainability in Earth Building systems.

I now know any individual is capable of this, all one needs to do is try in any one rural area at least once in a lifetime. What was true over a decade ago, is true even now! Just that now, Gram Disha Trust endeavors to help anyone who approaches it for enabling such systemic change. Interestingly most Earth Building architects were engaged in projects such as Sambhavna (Kangra/Dharamshala area), which was able to fund these resources through wealthy individuals – from other countries or even from Delhi. But rural pockets such as Pangna were not ‘fit enough’ for these resources to hazard and support – even if funds were provided. This was bordering techno-hypocrisy in my view at the time, but such is the truth of engagement for sustainability in Himachal. Eventually the Design set by Suresh Vaidyarajan was to be continued forth.

More than the iterative solutions to challenges, the overall Problem was beginning to emerge. The issue of sustainability in Rural Habitation was undergoing disrepair. All village folk wanted a ‘pucca’ house made of RCC – even if it sent them to debt and penury. The Five Lakshan of a Habitat, were at the edge of decimation. The effort at Gram Disha was simply to engage, retain and hopefully revive, all the while Documenting the journey and process going along. It just so happens that a few well wishers witnessed these events in parts – sort of like seeing trailers of a movie – but the big picture is being documented only now.

January - May 2014 - The Building Process Begins

The process of layering the stone bricks, the Kohni and Bandh stones was interesting to say the least, as I had to leave for meetings and events outside India during this timeframe, I was able to record only partial aspects of the layering by the stonemasons. The results show that they were good. All the while, the villagers around the area did peek curiously, as to ‘What’ was being built here. Some said it looks like a Water Tank, some said that a crazy ‘Delhi-wale’ was building a house. All the talk made for amusing hearings. The local carpenter provided the Door and Window frame through ‘proper purchased invoices’ for wood. It was important to indicate to the local population that no corners were being cut or regulations being bypassed to develop this structure. It took an effort of almost – 5 months – to build this structure, some attributed to the complexity of structure, decisions from my side on procurements, availability of labour for the mason and ‘many other reasons’.

It was difficult to explain what the plan was for Gram Bhawan, best was to let it all unfold. The villages of India are still quite simple in nature, they cover themselves with ideas of Urban Habitat systems with ease, therefore the outlier idea of creating spaces for deliberation on Rural Craft and Culture was also difficult to understand. It is also the case that during this time the institution ‘Gram Disha’ was not born. The ideas were just emerging. Meanwhile, the work with Farmers on Non-Chemical agriculture was progressing, the first PGS ( Participatory Guarantee Systems ) groups were formed in the Pangna valley – and a few other locations in Himachal by JaivikHaat.

Now that the walls were done, the door and window frames were placed, what next, but the roof. At the time I had no idea how tricky this could get, and why it is important to understand ‘Design and Architecture’ by the ‘client’ rather than just rely on the ideas of the Architect. It was good learning and an interesting time. It was also revealing, when friends started to indicate the wrong decision of having gone ahead with a Senior architect, who was trying to impose his design ideas at our expense. That failure to complete this will be a disaster waiting to happen. I realised that for programs such as this – where the outcome is non-deterministic – the world around you waits for you to fall and fail. This is not what happened here, though the process did have its fair amount of pain involved.

At all points in time the basic principles remained – No Cement or RCC, Modern Design but local craft and materials and the purpose of the outcome. These points were beginning to come to loggerheads with the ‘Modernised’ idea of construction. At times the architect also, despairing indicated – ‘Inke Bas Ki Nahin Hai‘ (They – local masons – do not have the capacity) towards fulfilling his designs.

November 2014 Onwards

At this stage, for the roofing, the choice of natural material in Himachal Pradesh – and specifically around the Pangna Valley were the following –

- Timber – purlins and rafters

- Stone – layering

- Bamboo – Purlins and rafters

- Brick – but the kilns were at a distance higher than the above

Now the challenge was to find the materials solution which shall be strong to hold the roof weight, low maintenance (as rise of the roof shall be higher due to the span of the Gram Bhawan), affordability in material access, craftsperson usability (as depending on the material the availability of the mason/craftsperson may be challenging), satisfaction of the architect and myself. As timber was an expensive option for the Roof Span, it was soon eliminated as a material of choice. The next option was Bamboo. Sachin Sachar supported the process of design for the roof with modeling and drawings.

This helped narrow it down as an option. Meanwhile we also got in touch with the present Bamboo Man of India – Vaibhav Kale (Of WonderGrass) – who is also a friend.

The problems with Bamboo became apparent in the next 3 months – the Bamboo species was Himalayan Maggar (Dendrocalamus somdevai/Hamiltonni), strongly susceptible to Borer. There was no support available for Boucherie treatment at our site. A lot of experts indicated that we could DIY but no one came forward to support the process. Vaibhav offered to ship the stronger Dendrocalamus Strictus from Maharashtra along with technical Expertise based on a Turnkey project. This was a perfect for us, except that the cost shall escalate and timeline availability of his team was unknown. It was also an issue for us that it would not be a sustainable solution if we were to ship Bamboo over 1500 km from across India to Himachal. We could not grow the useful species of Bamboo ourselves as it would take at least 6 years or more before the Bamboo may be ready, if it grew at all!

The process lasted for about 3 months or so, all the while the structure was roofless. Meanwhile, I got a chance to travel across many countries for conducting Trainings and events on Organic Agriculture till about February 2016. This entire span of time of about 1.5 years the structure stood without any roof or solution. Multiple discussions with Earth Building organisation, experts and even our Architect did not yield any positive solutions towards ‘Sustainability’ benchmarks we had set for ourselves. Situation ahead was unclear and it was a tough time – and a long time period.

Meanwhile, it was discussed and discovered that no matter what roofing solution is done, the holds to the wall should have been either built into the wall during construction. In the absence of these, a Ring Beam shall have to be built to transfer the load of the Roof onto the wall. The other option was to build Columns of Wood or stone around the periphery of the Gram Bhawan, which while creating aspects of shade and shelter shall also provide load bearing. Simple designs showed that the latter may also not be feasible given the span which may result in a wall structure too high or the columns too wide for the space available on site.

Thus the idea too was dropped. Now began the first loss of sustainability where Urbanised Design countered the idea of sustainability very strongly. It was only now that one realised that the fault also lay in the mind of the architect – who are themselves limited by the very idea of sustainability or just trade-off materials with ease in design.

Suresh started strongly recommending that RCC shall have to be used in the Ring Beam. This aspect shattered the idea that ‘complete’ modern structures and designs are possible with Earth Building and Natural Material. Eventually I had no choice but to concede ‘failure’ and accept RCC to build a ring beam. My hope was that the ring beam may also support the bamboo or timber roof, but that was not to be.

My alma mater – BITS Pilani ran an Innovation program called Parishodh which referred to a very diligent individual Vamshi Krishna, an Engineer from Andhra Pradesh. His efforts were instrumental in the development of the Ring Beam, on which the roof rests today. His report is still a testament to the effort.

It is important to note that anyone who wishes to build with a ‘Puritan’ view of Earth Building, should either rely only on the masons or craftspersons in the area who – due to lack of resources or availability/affordability of architects/designers – work with what they have or collaborate with an architect who may understand these concepts more deeply.

In my experience the latter are very few in India – and if they exist they are unwilling to collaborate.

The only one architect of this order in my experience is Anshul Walia (Diksha), also our Trustee, who has also been instrumental with a number of works at Gram Bhawan, majorly the Gharats of Himachal Pradesh. Readers may also be able to find Dikshas work interventions on Gram Disha website. I still look forward to working with Diksha on interesting aspects of Rural Intervention in Design and Architecture. Hopefully in future there shall be other such outputs to share. This only goes to show that the entire techno-educational domain in India still lacks its expertise for the country. Most only chase Urban projects and big money, hardly anyone supports the experience.

For me it was also a life lesson on how to engage with professionals who may have the intent or inclination to support the process but lack the courage to see through it by themselves. If the process is successful they take the credit, if it fails, well it was the clients fault!

March 2016 Onwards - Vault Construction

Now it took deliberations of 8 months more – of a roofless Gram Bhawan – to finally concede to the recommendations of our Architect Suresh ji. The bamboo roofing was no longer an option, even though cost wise it was about the same. Suresh had built Vaults before, it was even identified as his design idiom of choice. The thing was that Vaults were not the Cultural Idiom of Himachal Pradesh. In any case RCC had been used for the Ring Beam to transfer the weight of the roof.

It was also a challenge that there were no masons who knew how to lay a vault in Himachal Pradesh. We were also locked into the dodecahedron of Gram Bhawan so the span was also a challenge to overcome. Suresh had worked in the past with a mason named Shoiab, who was an expert in Dome and Vault constructions. Shoiab and Suresh designed a Protractor to enable uniform layering of the dome. It was a large span for a protractor, and getting it to site was also a challenge. Suresh suggested tying it to the roof of the car, but that would have led to traffic problems. Thus the protractor was split into members for reassembly on site. I carried it to the site in Himachal Pradesh from Delhi. This protractor would then be the single most important tool for the uniform layering of bricks for the ‘Stupa’ like design of Gram Bhawan. The Protractor was to be mounted on a 21′ steel pole at the vertex of the Gram Bhawan. This raised the protractor to a level where the roof layering could be gradually done.

It was also clear that the weight of the stone blocks may not be suitable for the vault layering as the weight of the blocks may be too much for the walls and ring beam to bear. Kiln baked Clay bricks would have to be the material of choice. These were procured from within Himachal Pradesh but from Kilns in the Lower areas between Parwanoo and Nalagarh, adjoining Punjab. It was a trade-off which I had hoped to avoid in place of Natural Building materials for Gram Bhawan, but had given in to the situation and conditions. Eventually Gram Bhawan now is a unique structure and has developed a history with the region, on its own. It is also the logo and symbol of Gram Disha Trust.

Shoaib, further referred to Parimal – who is till today a source of inspiration for me. This man with a petite frame, Parimal, is a hard working genius! Hailing from a village in Bengal-Bihar border, Parimal and his brother travelled with me to the Pangna valley to complete this unique task. It was Parimal’s confidence which I finally reflected upon to complete this task. Parimal teamed up with the ageing stone mason who built the walls of Gram Bhawan, Brij Lal and created a wonder in the land!

The local Bamboo came in handy to create a platform which the team of masons eventually customized to create a platform to work with. The platform was gradually raised to allow the brick layering to take place at an increasing height.

The curiosity of the villagers turned into marvel, when they ‘saw’ a roof being built without shuttering. It was unheard of and the local masons had no inkling of how it could be done. The only way to create this structure was to build it and let the process speak for itself.

The curiosity of the process was also met with questions regarding the stability of the structure.

Well, it has now completed almost 9 years and Gram Bhawan still stands as a singularity and a testament.

The structure took just under one month to complete. The effort of Parimal must be lauded here, for it was his singular leadership which brought about this transformation. At the time, I was to travel to different countries for work with International Organisations, so getting photos was a challenge from the site. Parimal did his best at keeping me informed. Suresh and Shoaib also did their part of guiding Parimal on adding more mortar between bricks.

I did have a question at the time – towards the final waterproofing capacity of the Vault. Nothing is perfect! But aspects are manageable. The structure had to have a living engagement with the village, which it does till date. Looking from afar many villagers thought that the structure was a Water Tank, some even curiously concluded that it was a Mosque. Now, I guess Gram Bhawan is a little bit of everything – in time and space!

Once the structure was completed Parimal brought the entire village – 7 families – Kids and all. A total of about 30 persons or so, were pushed to stand on the roof and convince themselves of its stability.

I had specifically requested that Parimal leave the top of the Vault as a sun roof. It was also the case that Gram Bhawan did look like a water tank from afar! Therefore I decided that the topping of this cake should be a vernacular design ventilator and sunroof. The local welder was called in to provide the Iron Angles and place this with the glass in place. The glass and iron angles were also, in this sense, materials from outside the radius, however, they do have an element of reuse.

Parimal understood this well enough and constructed a beam at the circumference at the very top of Gram Bhawan. It is this aspect which gives Gram Bhawan its unique mountain character. Slate is available in the mountains and is a part of life and habitat. It was also decided that this material shall also be used in the design. Slate is a versatile building material, from use for roofing tiles, flooring it can also be used for skirtings and wall tiles. The material is mined in the Mountains and is part of Himachali Habitat culture for centuries. Slate functions well in winters with heat retention and is cool in summer. There are licensed suppliers who provide this in and around the Pangna valley so accessing the material was easy.

I had specifically requested that Parimal leave the top of the Vault as a sun roof. It was also the case, that Gram Bhawan did look like a water tank from afar! Therefore I decided that the topping of this cake, should be a verncular design ventilator and sun roof. Parimal understood this well enough and constructured a beam at the circumference at the very top of Gram Bhawan. It is this aspect which gives Gram Bhawan its unique mountain character. Slate is available in the mountains and is a part of life and habitat. It was also decided that this material shall also be used in the design. Slate is versatile building material, from use for roofing tiles, flooring it can also be used for skirtings and wall tiles. The material is mined in the Mountains and is part of Himachali Habitat cultural for centuries.

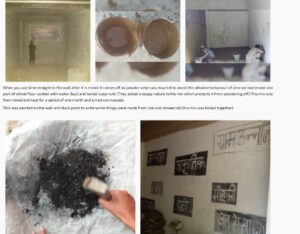

As I had indicated before, waterproofing was also a concern since I was absolutely clear that no more cement or RCC shall be used in the construction.

Thus the walls had to be mud plastered and needed to be protected from the High incidence of rain which this valley experiences. While the slope of the roof is fine, there are places where there still is seepage. Two coats of TAPCrete did not eliminate this till date, and we have learnt to live with this as a limitation of the design. There also is a plan to lay slate on the roof, but the estimates of cost and complexity are still to be worked out. Frankly, I am happily tired of the process of undertaking this on my own now. Perhaps there will, yet, be an opportunity for interns in the future to undertake this and many other exciting processes of Earth Building and craft at Gram Bhawan in the future.

Thus two more elements were introduced: a roof skirting to protect walls from rain and a raised floor sitout skirting around Gram Bhawan to prevent surface water from seeping up. Slates were used in both these construction pieces. These too contributed to the overall look of Gram Bhawan as a ‘Himachali’ of mountain structure while contributing their functionality.

At this point it is important to remember, that the road head or state highway 13 was a good 400 metres away from the village. Even though in 2021 there is a dirt road to the village back in 2015 all the material had to carted from the road head by Mules or on Human Back. this meant that slates, bricks and any natural material also had to be manually carted to the site. One may say it is the labour of love that we managed to build this space at Village Baag in the Pangna Valley and are able to have held many trainings and capacity building workshop with the farmers. Interestingly now that the road is built and trucks can enter up to the farm, no structure has been built since 2020 at Gram Bhawan. Perhaps there will be opportunity in the future, but I would not recommend anyone go through the same grind as I have, unless they have a careless zeal and lazy risk to do so. Suffice to say, that labour does help build character since only then does one realise the effort it takes. It is rather easy to pay money to someone else to build a habitat, it is quite another effort to build one on ones own or even contribute with one’s own hands. Working with knowledgeable craftsperson is learning to a different degree.

December 2016 Onwards

In 2016, Gram Bhawan also saw the arrival of two students from Germany – Arne Belier and Mathis Bullinger. There was a good opportunity to create an engagement activity between the village folk and the students. They were to stay a full year. Now the interesting bit was that the Village folk did not speak any English and the students spoke with an accent. I decided to let the activity unfold into interactions.

As the students intended to stay at Gram Bhawan, the next logical structure to build was a Toilet and Bathroom. The village folk were responsible for the hospitality of Arne and Mathis, so food was taken care of. Till the time the toilet and bathroom were built both were put up at a small guest house by the road side in the Pangna Village. Again, I was keen on not having to use any Cement or RCC in the construction. Having learnt many lessons on the building of Gram Bhawan, I decided it was best not to consult any architect for these structures and rely on the local knowledge and materials.

The masons and craftsperson, having built Gram Bhawan, were also keen to engage on other structures – some of it as a novelty and also to continue gaining occupation paid for from my side or projects. Gram Disha Trust was not founded by this time, that happened only in 2018. Until then, I had to raise funds for these activities on my own or through projects.

The point about the toilet was handling of the sewage and human wastes. The decision started from here. As it was decided not to build a classic septic tank in RCC, the villagers were clueless on what other options could exist. Having hiked across mountains I knew that makeshift toilets were common, but the techniques were not known. I decided to seek knowledge from India’s well known NGO in this domain ‘Sulabh International‘. I visited the very unique but relatively unknown ‘Toilet Museum‘ run by the organisation in Delhi. From here I was able to connect with their staff in Chandigarh.

Sachin Sachar, accompanied me in these searches to determine ‘what’ could be the best solution for Gram Bhawan. Sulabh International must be credited here, their staff in Chandigarh was most kind and accommodating. They not only offered designs of the Soak Pit System but offered a Rural Pan completely free. An engineer from their Mandi office also visited the site to inspect and offer recommendations for the construction.

The local conditions and challenges to surpass were well understood – Land space was limited, human refuse could not be allowed in the open, composting could be an option but no one in the village was interested in ‘handling’ this. There had to be confinement of the wastes and could not be allowed to overflow or smell for reasons of hygiene. There had to be a mechanism for the land to soak in the fluids and the biodegradation to happen with ease.

It had to be collocated with Gram Bhawan so there is ease of access and use. In Ladakh at SECMOL, my volunteering was to recreate a Dry Latrine system. Now there was learning, but Ladakh the weather is markedly different from Himachal Pradesh. Therefore the same techniques could not be applied.

After a lot of deliberation and discussions after almost 6 months, the Toilet construction works started. A Twin Soak Pit with a Y-Junction box was to be installed. The rural pan from Sulabh was to be placed in a two room Bathroom and Toilet. The main structure was to be Dry Stone masonry with mud mortar. Som Krishan, a lead farmer in the valley and his father Sant Ram ji ( who once was the owner of this land ) took up the responsibility of the plastering of the walls. Brij Lal ji, the mason who built the Gram Bhawan walls took to constructing this structure as well. The slates were placed by a craftsperson downstream from Pangna valley village called Chandiyara. The village folk of Baag also supported the process, this was all done through payments done – partly on Theka or contract and partly through Jawari or communal labour.

The works slowed down for a bit due to Winters and snow but in about one month the Toilet and Bathroom was in place. It is another matter – which still exists – on fresh water availability from Government sources. The availability of water is still sketchy till date. The village manages with fresh water from the river or nearby springs.

This works, no matter what the opinion against this is otherwise. The fact that German students managed with this for one whole year is a testament in itself. While cleanliness and hygiene can only be inculcated and not taught, the village folk also used the toilet for quite a while until it became a challenge keeping it clean. TIll date a number of events take place at Gram Bhawan the Devi-Devta collectives also stay at Gram Bhawan and 20-30 people are comfortably able to utilise the facilities at a stretch. The Y-junction has not been switched till date and the soak pit continues to serve its purpose even after 9 years of functioning, at the time of writing this article in 2025. Bhupender (who we know as Moongi) has been associated with this process since he was a kid. Now, married with kids, he is also caretaking Gram Bhawan and managing the farm as well. Khub Ram, Moongi’s father, is the gentleman of the village. He was also contributed with deeper engagement connecting with the intent of Gram Bhawan. The future unfolds till date and we are waiting to see how this helps Moongi develop well as an individual through this engagement.

February 2017 Onwards - Until August 2017

Arne and Mathis also undertook construction of other structures with the craftsperson. This was the kitchen and the Horse shed. One of the tasks which the student volunteers had was taking care of a horse at Gram Bhawan.

The horse shed was to be built for this purpose. At this point it was also clear that at least one example of Rammed Earth Structure also called Matkaandaa, in Himachal Pradesh was also to be built to keep the craft alive and document the process. Here again, Som Krishan and his team took charge and decided to throw themselves to the task.

Plans are easy, but the Farm and the land sets one on an onerous task. It is almost like a Tapasyaa at times. The plan was to create a levelled platform, however, upon digging it out, there are buried boulders of sizes enough to daunt the expert of all Masons. While this was advantageous initially that stone for the retaining walls and building could be extracted from them, the boulders were deeper than one initially imagined. The diggers and masons were set to task along with the student volunteers. While the results today are quite a sight to see, at the time it was one challenge thrown after another just to level the ground and prepare it for the kitchen and horse shed.

Since that time until 8 years hence, at the time of writing this article in 2025, the structures still stand and are in utility with the village community. Yes, there is a living engagement with these structures but they have a sustainable usability quite unlike with Urban buildings built with Steel and Cement – both of which are unsustainable. At this moment, with the data available, even with the sincerest desire of the Industrial System – at least in our generation sustainability cannot be achieved by it. They will continue to pollute and cause global warming no matter what justification is given. Earth Building systems – combined with modern methods are truly sustainable in the meaning of the word. It is also a challenge to create the infrastructure and knowhow in India where such a system may be learnt from and supported not just in Rural areas but Urban spaces too.

The images below speak for themselves and the effort of the last 13 years to live, build and experience these community engagements in Himachal Pradesh. It is now clear that when it comes to sustainability, it is not Rural India that has to catch up with modernism, quite the opposite really. There is a question of scale here, which is also clarified that land and its availability is not an issue in India. The population density of cities is the main problem here, not the population of India at large.

Perhaps there may be future generations of Earth Builders, architects whose availability for rural Indian communities – anywhere really – will be as common for the Rural population as much as Billionaires in cities. But at least in my generation such experts are not present or available. Which is also why Rural India continues to function, as it did, for centuries based on the material, design and craft available in its surrounding geography. This is actually the core of sustainability in any country across the world.

Readers are also encouraged to read other aspects of Earth Building and sustainability at Gram Bhawan – which are mainly led by our co-trustee – Diksha (Anshul Walia). These include the Gharat – Water Mills and its documentation, Stone pavements, Bamboo Screens and an ‘Organic Shop’! (Click Specific Image for Direct links to articles online).

These also provide glimpses on what is possible, I leave it to the reader to decide if it is feasible for them, based on their idea of Sustainability. At least in my mind, I am now clear what this is all about – and more importantly – what it is not!

Perhaps it is good to revisit the 5 precepts of Building Habitats which vernacular craftspersons and historians have left with our generation.

- Prakriti se prem karwaye – Inculcates love for nature

- Arthik Roop Se Sahayak ho – Helpful in the generation of wealth or continuously lowering the expense.

- Arogya ke Lie Sreshth ho, Jahan Paon Garam, Pet Naram aur Sar Thanda rahe – Is best for one’s health

- Jo Samajik banaye – which allows one to remain socially interactive.

- Adhyatmik Disha mein le jane wala ho – Leads one towards Spiritual goals and achievement.

Does your habitat – place of work – allow for all 5 of these precepts to be met? Remember it is easy to justify one’s situation to satisfy the above, but from the aspect of Truth, it is actually quite difficult.

Now this is the condition of someone with a moderate amount of Education, a privileged middle class upbringing and moderate amount of wealth/money. When we cannot get assistance from all the architecture of the world, what hope can a common villager have who has to build a habitat for one’s family. All the ‘so called’ knowledge comes to a naught if it cannot work for the common folk. At that point knowledge becomes information, which is easily available across the world today. What of it? Just blaming the government or society is not enough for this condition, one must look deeply into oneself and determine where the fault lies. Big architects may build Billion dollar structures to gain name, fame and wealth, but to my mind they are worth a naught if they cannot – in their lifetimes – build even one structure for the common village folk – as deeper learning on gratis. Such pro-bono architects do not exist today! At least in our experience they do not.

Today there is big talk of Sustainability and decarbonising cement, but it is just that talk. The 4 R’s of Sustainability may as well apply here – Reuse, Reduce, Recycle, Rejuvenate and Refuse. All these apply within Earth Building Systems.

For me, the village where Gram Bhawan is, if it has no access to those who wish to learn and change, then the entire system is a total failure, no matter what others say. This experience in Sustainability in Rural Himachal Pradesh is a valuable one, for it shows the reality of what a burden knowledge can be when it cannot be applied for common rural folk. Eventually it will diminish with time no matter how tall and fancy Urban buildings may become. Not one architect worth their salt – till date – is capable – in my experience – but some come close to walking the path. Those who helped Gram Bhawan get this far are credited for its existence not just till today – but perhaps to the following lifetimes even – as Punya merits they carry. Indeed all of the above requires extraordinary courage to undertake – therefore those who do not should be, then, considered ‘ordinary’ no matter what burden of information they carry.

Eventually the idea is that these experiences reach the next generation. Perhaps, they may convert these ideas into better human symbiosis with nature. One of the key thoughts in mind with Gram Bhawan was also its end of life. The theory was – supposing Gram Bhawan was to be brought down, what will be the fate of its raw materials? Well the mud plaster may go back to the farm to grow crops again (part of the soil), the stone blocks may be reused by other people or even to build or improve terraces. The wooden frames may be reusable or at the very least be used on a funeral pyre, the glass – if it survives then it may be reused or if shattered may be converted to tools or placed as embeds in floors or walls by a designer of quality. Even the foundation rocks may be reused. What good would have been to the end of life of an RCC building? I leave this question as rhetorical for the coming generations to decide.

One remains hopeful that experiences such as this, may lead to a modicum of change in the understanding of Sustainability in its true meaning of the word. It is either this or a total and hopeless collapse, that we all foresee but not one wants to live to tell!